How Helen Frankenthaler Taught Color to Speak

By Emilia Novak

When Helen Frankenthaler first laid a raw canvas on the floor of her studio in 1952 and began pouring thinned paint across its surface, she could not have known she was changing the direction of modern art. At just twenty-three, she invented a new pictorial language—one that replaced the gestural intensity of Abstract Expressionism with something luminous, atmospheric, and quietly radical. Her soak-stain technique, developed in a moment of daring experimentation, would open the door to Color Field painting and inspire a generation of artists to reimagine what painting could be.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Helen Frankenthaler was born in 1928 into an intellectually affluent Manhattan family. Her father was a New York Supreme Court judge, and she grew up surrounded by culture and ideas. She studied at the Dalton School under the Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo, then at Bennington College, where she received a rigorous grounding in modern art.

After graduation, she immersed herself in New York’s burgeoning postwar art scene—a heady, male-dominated world shaped by figures such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko. She studied their canvases closely, absorbing Pollock’s revolutionary method of working on the floor and Rothko’s luminous color fields.

Equally important was her relationship with the influential critic Clement Greenberg, who became both a mentor and, briefly, a romantic partner. Greenberg introduced her to key artists and ideas, encouraging her to push beyond imitation and develop her own voice. She did—decisively.

The 1952 Breakthrough: Mountains and Sea

The turning point came after a trip to Nova Scotia. Inspired by its rugged landscape, Frankenthaler returned to New York and unrolled a large, unprimed canvas across the floor of her studio. Instead of applying paint with brushes, she thinned her oils with turpentine until they were almost translucent and poured them directly onto the fabric.

The paint soaked into the canvas, spreading in unpredictable, organic shapes. Sometimes she tilted the canvas to guide the flow; other times she used sponges or rollers. The result was Mountains and Sea (1952), a seven-foot-tall, airy composition of blues, greens, and pinks. It evoked land and water, but in a way that felt diaphanous and dreamlike rather than literal.

Critics were initially puzzled. Frankenthaler herself joked that the painting looked to some like “a large paint rag, casually accidental and incomplete.” It didn’t sell. Yet among artists, its impact was immediate. Frankenthaler later described the sensation of discovery:

“It melted into the weave of the canvas and became the canvas. And the canvas became the painting. This was new.”

Inventing a New Visual Language

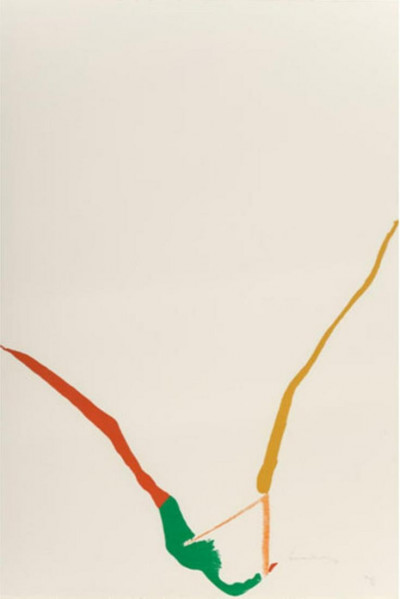

At that time, Abstract Expressionism dominated the avant-garde. It was the era of heroic gestures and muscular paint handling, a style largely defined by male artists. Frankenthaler’s technique was a quiet revolution. Inspired by Pollock’s floor painting but rejecting his aggressive splatters, she created something lighter and more fluid.

Her soak-stain method transformed paint from a layer resting on the canvas into something that became inseparable from it. She wasn’t just painting a surface; she was saturating it with color, allowing paint and canvas to fuse into a single entity.

This approach offered a new way to think about abstraction—one that emphasized color, atmosphere, and permeability rather than gesture and mass. Her innovation was subtle but seismic: a bridge between Abstract Expressionism and what would soon become Color Field painting.

The Spark That Ignited a Movement

In 1953, Clement Greenberg brought Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland, two painters from Washington, D.C., to visit Frankenthaler’s studio. There they saw Mountains and Sea unfurled on the floor. They were stunned.

Louis later called the painting “a bridge between Pollock and what was possible.” Back in Washington, Louis and Noland began experimenting with pouring thinned paint onto raw canvas. Their subsequent works—Louis’s Veil and Unfurled series, Noland’s iconic targets and chevrons—became cornerstones of the Color Field movement.

These artists moved away from the turbulent energy of Abstract Expressionism, focusing instead on broad, serene fields of pure color. Louis and Noland both acknowledged Frankenthaler’s innovation as the catalyst. Her studio became, quite literally, the place where a new movement began.

Evolving the Soak-Stain Method

Frankenthaler continued to refine her technique over the following decades. Around 1962 she transitioned from oil to acrylic paint, which soaked into the canvas similarly but dried more quickly and allowed for greater control and vibrancy.

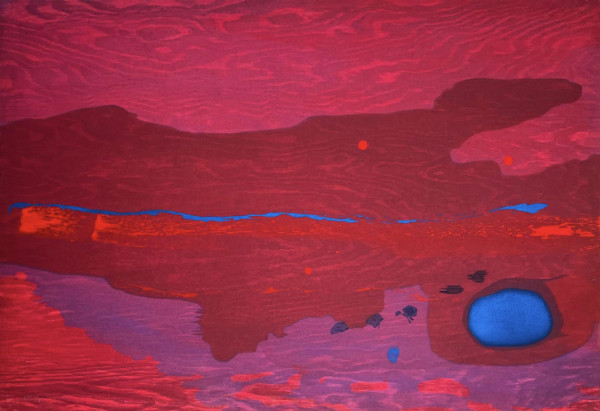

Her 1963 painting The Bay is a prime example of her mature style: a single, bold blue shape blooms across the canvas, surrounded by soft, translucent veils of color. She described the canvas as an open field—a space where colors could “bleed into one another” organically.

Her approach inspired critics to use new language to describe this wave of abstraction. Clement Greenberg coined the term “Post-Painterly Abstraction” for his 1964 exhibition that featured Frankenthaler alongside Louis, Noland, and others. This style emphasized clarity, openness, and the emotional power of color itself.

Navigating a Male-Dominated Art World

Frankenthaler’s rise was all the more remarkable because she achieved it in a deeply male-dominated art world. The New York School of the 1950s celebrated male genius; female artists were often overlooked, their work diminished with faint praise.

Frankenthaler, however, commanded attention through the originality of her painting. She had the confidence of someone well educated and culturally connected, but more importantly, she had the courage to innovate.

Critics sometimes labeled her work “pretty” or “decorative,” terms that carried dismissive undertones when applied to women’s art. She refused to be boxed in, embracing beauty and lyricism as deliberate artistic choices.

“There are no rules. That is how art is born… Go against the rules or ignore the rules. That is what invention is about,” she declared.

Her success helped pave the way for future generations of women artists, from Joan Mitchell to contemporary painters who continue to challenge and redefine abstraction.

A Life in Art and Partnership

In 1958, Frankenthaler married fellow abstract painter Robert Motherwell. They became known as the “golden couple” of the art world, hosting salons where ideas flowed as freely as wine. Their marriage lasted until 1971. While both were celebrated artists, Frankenthaler’s creative identity remained fully her own.

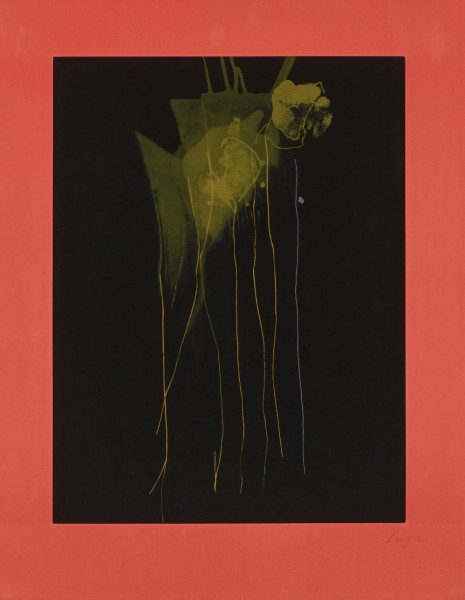

Throughout the 1960s, 70s, and beyond, she maintained a rigorous studio practice, constantly exploring new formal possibilities. She worked across media—painting, drawing, and printmaking—with a spirit of continual experimentation.

Enduring Influence and Market Legacy

Frankenthaler’s soak-stain technique reshaped painting, influencing not only her immediate contemporaries but also generations of artists after them. Painters such as Jules Olitski, Sam Francis, and Richard Diebenkorn all extended her ideas in their own ways, exploring luminous color fields and open compositions.

Her influence persists today in contemporary abstraction. What was once radical—pouring thinned paint onto raw canvas, embracing chance—has become a common artistic language, thanks to her pioneering example.

The art market has also recognized her importance. Major retrospectives at MoMA and the Whitney cemented her reputation, and in 2001 she received the National Medal of Arts. Her paintings have achieved steadily rising auction prices, with large-scale works from the 1970s particularly prized for their bold colors and mature style. Sotheby’s experts have noted that a new generation of collectors is drawn to her work not only for its beauty but for its historical significance.

Frankenthaler was also an accomplished printmaker. Her monumental woodcut Madame Butterfly (2000) is widely regarded as a masterpiece of contemporary printmaking. Composed of 46 woodblocks and 102 colors, it spans over six feet and achieves extraordinary subtlety and harmony. It stands as a testament to her relentless creative ambition, even late in her career.

A Legacy Written in Color

Helen Frankenthaler once said,

“A really good picture looks as if it’s happened at once. It’s an immediate image.”

That immediacy is what makes her paintings so powerful. They feel fresh, spontaneous, and inevitable—as if they simply appeared fully formed. She expanded painting’s vocabulary not by rejecting the past, but by transforming it.

Frankenthaler’s legacy is everywhere: in the luminous canvases of Color Field painters, in the techniques of countless contemporary artists, and in the collections of museums and private patrons worldwide. She demonstrated that color alone could carry emotional weight, and that invention sometimes comes in a quiet, fluid gesture rather than a loud declaration.

By pouring paint onto a canvas one afternoon in 1952, Helen Frankenthaler changed the course of art history. She bridged Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting, broke through gender barriers, and left behind a body of work that continues to glow with intelligence, daring, and lyric beauty.

By Emilia Novak

When Helen Frankenthaler first laid a raw canvas on the floor of her studio in 1952 and began pouring thinned paint across its surface, she could not have known she was changing the direction of modern art. At just twenty-three, she invented a new pictorial language—one that replaced the gestural intensity of Abstract Expressionism with something luminous, atmospheric, and quietly radical. Her soak-stain technique, developed in a moment of daring experimentation, would open the door to Color Field painting and inspire a generation of artists to reimagine what painting could be.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Helen Frankenthaler was born in 1928 into an intellectually affluent Manhattan family. Her father was a New York Supreme Court judge, and she grew up surrounded by culture and ideas. She studied at the Dalton School under the Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo, then at Bennington College, where she received a rigorous grounding in modern art.

After graduation, she immersed herself in New York’s burgeoning postwar art scene—a heady, male-dominated world shaped by figures such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko. She studied their canvases closely, absorbing Pollock’s revolutionary method of working on the floor and Rothko’s luminous color fields.

Equally important was her relationship with the influential critic Clement Greenberg, who became both a mentor and, briefly, a romantic partner. Greenberg introduced her to key artists and ideas, encouraging her to push beyond imitation and develop her own voice. She did—decisively.

The 1952 Breakthrough: Mountains and Sea

The turning point came after a trip to Nova Scotia. Inspired by its rugged landscape, Frankenthaler returned to New York and unrolled a large, unprimed canvas across the floor of her studio. Instead of applying paint with brushes, she thinned her oils with turpentine until they were almost translucent and poured them directly onto the fabric.

The paint soaked into the canvas, spreading in unpredictable, organic shapes. Sometimes she tilted the canvas to guide the flow; other times she used sponges or rollers. The result was Mountains and Sea (1952), a seven-foot-tall, airy composition of blues, greens, and pinks. It evoked land and water, but in a way that felt diaphanous and dreamlike rather than literal.

Critics were initially puzzled. Frankenthaler herself joked that the painting looked to some like “a large paint rag, casually accidental and incomplete.” It didn’t sell. Yet among artists, its impact was immediate. Frankenthaler later described the sensation of discovery:

“It melted into the weave of the canvas and became the canvas. And the canvas became the painting. This was new.”

Inventing a New Visual Language

At that time, Abstract Expressionism dominated the avant-garde. It was the era of heroic gestures and muscular paint handling, a style largely defined by male artists. Frankenthaler’s technique was a quiet revolution. Inspired by Pollock’s floor painting but rejecting his aggressive splatters, she created something lighter and more fluid.

Her soak-stain method transformed paint from a layer resting on the canvas into something that became inseparable from it. She wasn’t just painting a surface; she was saturating it with color, allowing paint and canvas to fuse into a single entity.

This approach offered a new way to think about abstraction—one that emphasized color, atmosphere, and permeability rather than gesture and mass. Her innovation was subtle but seismic: a bridge between Abstract Expressionism and what would soon become Color Field painting.

The Spark That Ignited a Movement

In 1953, Clement Greenberg brought Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland, two painters from Washington, D.C., to visit Frankenthaler’s studio. There they saw Mountains and Sea unfurled on the floor. They were stunned.

Louis later called the painting “a bridge between Pollock and what was possible.” Back in Washington, Louis and Noland began experimenting with pouring thinned paint onto raw canvas. Their subsequent works—Louis’s Veil and Unfurled series, Noland’s iconic targets and chevrons—became cornerstones of the Color Field movement.

These artists moved away from the turbulent energy of Abstract Expressionism, focusing instead on broad, serene fields of pure color. Louis and Noland both acknowledged Frankenthaler’s innovation as the catalyst. Her studio became, quite literally, the place where a new movement began.

Evolving the Soak-Stain Method

Frankenthaler continued to refine her technique over the following decades. Around 1962 she transitioned from oil to acrylic paint, which soaked into the canvas similarly but dried more quickly and allowed for greater control and vibrancy.

Her 1963 painting The Bay is a prime example of her mature style: a single, bold blue shape blooms across the canvas, surrounded by soft, translucent veils of color. She described the canvas as an open field—a space where colors could “bleed into one another” organically.

Her approach inspired critics to use new language to describe this wave of abstraction. Clement Greenberg coined the term “Post-Painterly Abstraction” for his 1964 exhibition that featured Frankenthaler alongside Louis, Noland, and others. This style emphasized clarity, openness, and the emotional power of color itself.

Navigating a Male-Dominated Art World

Frankenthaler’s rise was all the more remarkable because she achieved it in a deeply male-dominated art world. The New York School of the 1950s celebrated male genius; female artists were often overlooked, their work diminished with faint praise.

Frankenthaler, however, commanded attention through the originality of her painting. She had the confidence of someone well educated and culturally connected, but more importantly, she had the courage to innovate.

Critics sometimes labeled her work “pretty” or “decorative,” terms that carried dismissive undertones when applied to women’s art. She refused to be boxed in, embracing beauty and lyricism as deliberate artistic choices.

“There are no rules. That is how art is born… Go against the rules or ignore the rules. That is what invention is about,” she declared.

Her success helped pave the way for future generations of women artists, from Joan Mitchell to contemporary painters who continue to challenge and redefine abstraction.

A Life in Art and Partnership

In 1958, Frankenthaler married fellow abstract painter Robert Motherwell. They became known as the “golden couple” of the art world, hosting salons where ideas flowed as freely as wine. Their marriage lasted until 1971. While both were celebrated artists, Frankenthaler’s creative identity remained fully her own.

Throughout the 1960s, 70s, and beyond, she maintained a rigorous studio practice, constantly exploring new formal possibilities. She worked across media—painting, drawing, and printmaking—with a spirit of continual experimentation.

Enduring Influence and Market Legacy

Frankenthaler’s soak-stain technique reshaped painting, influencing not only her immediate contemporaries but also generations of artists after them. Painters such as Jules Olitski, Sam Francis, and Richard Diebenkorn all extended her ideas in their own ways, exploring luminous color fields and open compositions.

Her influence persists today in contemporary abstraction. What was once radical—pouring thinned paint onto raw canvas, embracing chance—has become a common artistic language, thanks to her pioneering example.

The art market has also recognized her importance. Major retrospectives at MoMA and the Whitney cemented her reputation, and in 2001 she received the National Medal of Arts. Her paintings have achieved steadily rising auction prices, with large-scale works from the 1970s particularly prized for their bold colors and mature style. Sotheby’s experts have noted that a new generation of collectors is drawn to her work not only for its beauty but for its historical significance.

Frankenthaler was also an accomplished printmaker. Her monumental woodcut Madame Butterfly (2000) is widely regarded as a masterpiece of contemporary printmaking. Composed of 46 woodblocks and 102 colors, it spans over six feet and achieves extraordinary subtlety and harmony. It stands as a testament to her relentless creative ambition, even late in her career.

A Legacy Written in Color

Helen Frankenthaler once said,

“A really good picture looks as if it’s happened at once. It’s an immediate image.”

That immediacy is what makes her paintings so powerful. They feel fresh, spontaneous, and inevitable—as if they simply appeared fully formed. She expanded painting’s vocabulary not by rejecting the past, but by transforming it.

Frankenthaler’s legacy is everywhere: in the luminous canvases of Color Field painters, in the techniques of countless contemporary artists, and in the collections of museums and private patrons worldwide. She demonstrated that color alone could carry emotional weight, and that invention sometimes comes in a quiet, fluid gesture rather than a loud declaration.

By pouring paint onto a canvas one afternoon in 1952, Helen Frankenthaler changed the course of art history. She bridged Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting, broke through gender barriers, and left behind a body of work that continues to glow with intelligence, daring, and lyric beauty.