Decoding Abstract Art: How to Approach and Appreciate Non-Representational Works

By Emilia Novak

Introduction: Standing Before the Unfamiliar

Imagine standing before a large canvas covered in sweeping strokes of orange and blue, or encountering a monumental steel sculpture that refuses to resolve into a recognizable form. For many, the first instinct is to ask: What does this mean? Abstract art often provokes such questions because it resists easy interpretation. Unlike representational works that depict familiar scenes, people, or landscapes, abstract and non-representational works invite us to experience art on a different plane—through form, color, texture, and rhythm.

To explore this terrain, we will consider several significant works of abstract and non-representational art: Eduardo Chillida’s Antzo VIII, Thomas Ruff’s Substrat 21 III, Alexander Calder’s Red Moon and Swirl, Ellsworth Kelly’s Orange and Blue over Yellow, Joan Miró’s Sobreteixims i Escultures, Pierre Soulages’ Eau-forte XXXII, Helen Frankenthaler’s Solar Imp, and Robert Motherwell’s Nocturne II (from the Octavio Paz Suite). Each of these artists, working in different mediums and traditions, opens a window into how abstraction operates and how viewers might approach its appreciation.

Abstract Art and Its Many Pathways

Abstraction is not a single style but a vast and varied field. It includes the lyrical washes of Abstract Expressionism, the geometric clarity of Hard-edge Painting, the gestural immediacy of Actionism, and the inventive surfaces of Tapestry and Sculpture. Many of the artists we will discuss have aligned themselves—loosely or firmly—with these movements, yet each developed a deeply personal vocabulary.

For the viewer, decoding abstract art is less about finding a narrative than about developing sensitivity to visual and material qualities. It involves asking: How does this composition make me feel? What rhythms, balances, or tensions emerge? How do color, texture, and scale alter my perception?

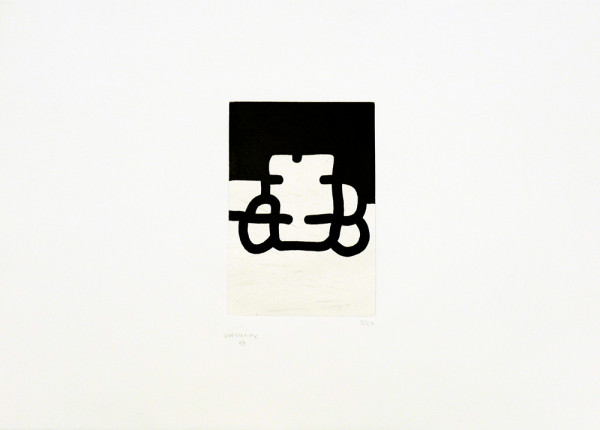

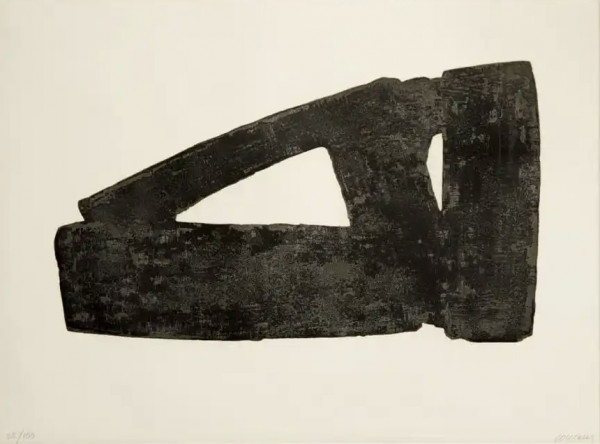

Eduardo Chillida – Antzo VIII: The Architecture of Space

Eduardo Chillida, a Basque sculptor, often worked in massive steel, creating works that engage space as much as material. Antzo VIII exemplifies his interest in architectural abstraction. Here, twisting and interlocking forms create a sense of weight and suspension, as though the sculpture were both rooted and in motion.

Chillida once remarked, “My whole work is a journey of discovery in space.” This guiding principle helps us approach his work not as an object with a literal subject, but as a conversation between volume and void. To appreciate Antzo VIII, we might walk around it, noting how light and shadow shift, how mass and emptiness interrelate.

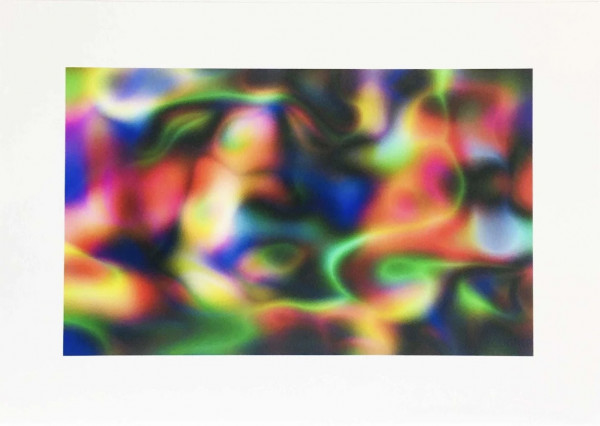

Thomas Ruff – Substrat 21 III: Digital Surfaces and Infinite Layers

German photographer Thomas Ruff’s Substrat 21 III pushes abstraction into the digital realm. The Substrat series was created using images sourced from the internet, digitally manipulated into luminous, swirling surfaces that seem to extend infinitely.

Here, abstraction arises from technology rather than paint or sculpture. What at first seems like a psychedelic cloud of colors is in fact an exploration of perception itself—what happens when visual information is stripped of context. Viewers are invited to let go of recognizable imagery and instead immerse themselves in the immaterial play of pixels and hues.

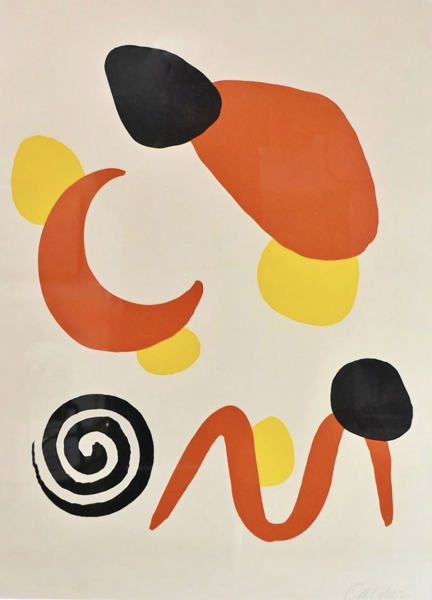

Alexander Calder – Red Moon and Swirl: Kinetic Vibrancy on Paper

Alexander Calder, best known for his mobiles, also created vibrant gouaches that echoed the energy of his sculptural work. Red Moon and Swirl demonstrates his affinity for biomorphic abstraction: bold, simple shapes rendered in striking colors.

Unlike Chillida’s heavy steel, Calder’s visual language is playful and airy. The red and black forms dance across the page, evoking movement and spontaneity. Approaching this work involves embracing its lightness—recognizing that abstraction can carry joy, humor, and rhythm without reference to external subjects.

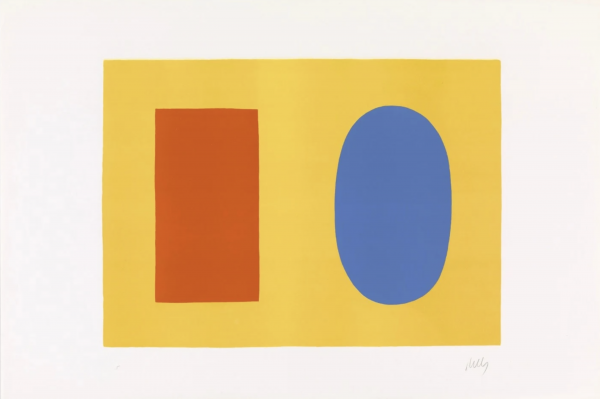

Ellsworth Kelly – Orange and Blue over Yellow: The Power of Color Alone

Ellsworth Kelly’s Orange and Blue over Yellow is a study in color relationships, stripped to their essentials. As a central figure in Hard-edge Painting, Kelly avoided gesture and personal expression, instead focusing on pure form and hue.

Here, the encounter is immediate and direct: large fields of orange and blue float above a yellow ground. To stand before such a work is to feel the intensity of color as a physical experience. Kelly invites us to abandon narrative entirely and simply see.

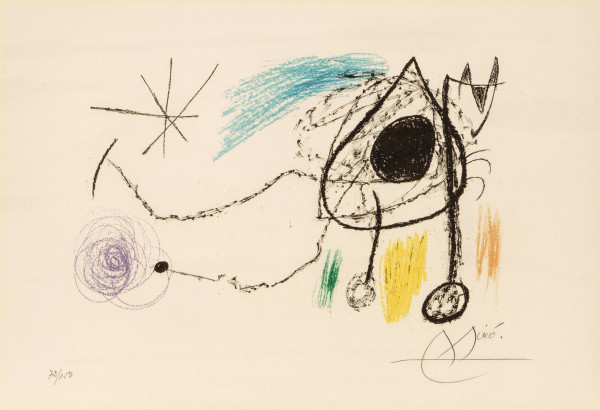

Joan Miró – Sobreteixims i Escultures: The Tactility of Abstraction

Joan Miró’s late work often combined painting, collage, and tapestry, expanding the surface into a multi-dimensional field. In Sobreteixims i Escultures, the Catalan master blurs boundaries between two-dimensional and three-dimensional art.

The rough textures and playful forms exemplify Miró’s connection to Automatism—an approach aligned with Surrealism, where chance and subconscious gestures guide the work. When engaging with this piece, viewers might notice how the irregular surfaces demand not just visual but almost tactile attention, shifting abstraction into a sensory encounter.

Pierre Soulages – Eau-forte XXXII: Black as a World of Light

French painter Pierre Soulages devoted much of his life to exploring the depth of black, a practice he called Outrenoir—“beyond black.” In his etching Eau-forte XXXII, black is not the absence of color but a dynamic surface that interacts with light.

The etched lines cut through darkness, revealing luminosity within shadow. To appreciate Soulages’ abstraction is to slow down and notice subtleties: how black reflects, absorbs, or releases light depending on angle and surface.

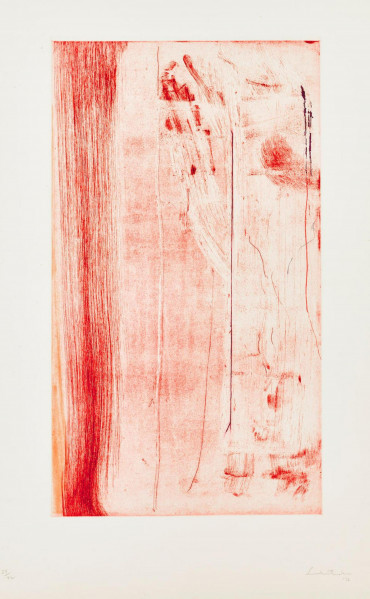

Helen Frankenthaler – Solar Imp: The Lyrical Flow of Color

Helen Frankenthaler, a pioneer of Abstract Expressionism and the Color Field movement, developed the “soak-stain” technique, allowing pigment to seep into raw canvas. In Solar Imp, broad, translucent washes of color spread like atmospheric phenomena.

Unlike Kelly’s precise forms, Frankenthaler’s abstraction is fluid and intuitive. Approaching her work involves surrender—letting the eye wander across expanses of color, noting how they bleed, overlap, and create depth. Her paintings remind us that abstraction can be as much about mood as about form.

Robert Motherwell – Nocturne II (from the Octavio Paz Suite): Poetry in Abstraction

Robert Motherwell, another key figure in Abstract Expressionism, often combined gestural abstraction with literary and philosophical influences. Nocturne II was part of a suite inspired by Mexican poet Octavio Paz, bridging painting and poetry.

Here, dark, gestural forms move across the surface with gravity and rhythm. To decode such a work is not to translate it into words but to sense its resonance—how visual marks might echo the cadence of poetry or the weight of silence.

How to Approach Abstract Art as a Viewer

When faced with non-representational works, the key is to release the expectation of narrative. Instead, consider:

- Form and Composition: How do shapes relate? Where is the balance or imbalance?

- Color and Texture: What emotions do colors evoke? What role does surface play?

- Materiality and Process: How does the medium—steel, canvas, print, or digital—affect your perception?

- Movement and Rhythm: Does the work suggest stillness, dynamism, chaos, or harmony?

Equally important is to notice your own response. Abstraction often functions like music: it may not depict anything directly, but it can stir profound emotional and sensory reactions.

Conclusion: The Open Invitation of Abstraction

Abstract art resists singular interpretation, and that is precisely its power. Works by Chillida, Ruff, Calder, Kelly, Miró, Soulages, Frankenthaler, and Motherwell demonstrate the breadth of non-representational expression—from heavy steel to digital flux, from vibrant color fields to black etched depths.

To decode abstract art is less about solving a puzzle than about opening oneself to an encounter. Each viewer brings their own perspective, memory, and feeling to the work. The reward lies in embracing this openness: allowing abstraction to expand our ways of seeing and feeling, offering us not answers but experiences.

By Emilia Novak

Introduction: Standing Before the Unfamiliar

Imagine standing before a large canvas covered in sweeping strokes of orange and blue, or encountering a monumental steel sculpture that refuses to resolve into a recognizable form. For many, the first instinct is to ask: What does this mean? Abstract art often provokes such questions because it resists easy interpretation. Unlike representational works that depict familiar scenes, people, or landscapes, abstract and non-representational works invite us to experience art on a different plane—through form, color, texture, and rhythm.

To explore this terrain, we will consider several significant works of abstract and non-representational art: Eduardo Chillida’s Antzo VIII, Thomas Ruff’s Substrat 21 III, Alexander Calder’s Red Moon and Swirl, Ellsworth Kelly’s Orange and Blue over Yellow, Joan Miró’s Sobreteixims i Escultures, Pierre Soulages’ Eau-forte XXXII, Helen Frankenthaler’s Solar Imp, and Robert Motherwell’s Nocturne II (from the Octavio Paz Suite). Each of these artists, working in different mediums and traditions, opens a window into how abstraction operates and how viewers might approach its appreciation.

Abstract Art and Its Many Pathways

Abstraction is not a single style but a vast and varied field. It includes the lyrical washes of Abstract Expressionism, the geometric clarity of Hard-edge Painting, the gestural immediacy of Actionism, and the inventive surfaces of Tapestry and Sculpture. Many of the artists we will discuss have aligned themselves—loosely or firmly—with these movements, yet each developed a deeply personal vocabulary.

For the viewer, decoding abstract art is less about finding a narrative than about developing sensitivity to visual and material qualities. It involves asking: How does this composition make me feel? What rhythms, balances, or tensions emerge? How do color, texture, and scale alter my perception?

Eduardo Chillida – Antzo VIII: The Architecture of Space

Eduardo Chillida, a Basque sculptor, often worked in massive steel, creating works that engage space as much as material. Antzo VIII exemplifies his interest in architectural abstraction. Here, twisting and interlocking forms create a sense of weight and suspension, as though the sculpture were both rooted and in motion.

Chillida once remarked, “My whole work is a journey of discovery in space.” This guiding principle helps us approach his work not as an object with a literal subject, but as a conversation between volume and void. To appreciate Antzo VIII, we might walk around it, noting how light and shadow shift, how mass and emptiness interrelate.

Thomas Ruff – Substrat 21 III: Digital Surfaces and Infinite Layers

German photographer Thomas Ruff’s Substrat 21 III pushes abstraction into the digital realm. The Substrat series was created using images sourced from the internet, digitally manipulated into luminous, swirling surfaces that seem to extend infinitely.

Here, abstraction arises from technology rather than paint or sculpture. What at first seems like a psychedelic cloud of colors is in fact an exploration of perception itself—what happens when visual information is stripped of context. Viewers are invited to let go of recognizable imagery and instead immerse themselves in the immaterial play of pixels and hues.

Alexander Calder – Red Moon and Swirl: Kinetic Vibrancy on Paper

Alexander Calder, best known for his mobiles, also created vibrant gouaches that echoed the energy of his sculptural work. Red Moon and Swirl demonstrates his affinity for biomorphic abstraction: bold, simple shapes rendered in striking colors.

Unlike Chillida’s heavy steel, Calder’s visual language is playful and airy. The red and black forms dance across the page, evoking movement and spontaneity. Approaching this work involves embracing its lightness—recognizing that abstraction can carry joy, humor, and rhythm without reference to external subjects.

Ellsworth Kelly – Orange and Blue over Yellow: The Power of Color Alone

Ellsworth Kelly’s Orange and Blue over Yellow is a study in color relationships, stripped to their essentials. As a central figure in Hard-edge Painting, Kelly avoided gesture and personal expression, instead focusing on pure form and hue.

Here, the encounter is immediate and direct: large fields of orange and blue float above a yellow ground. To stand before such a work is to feel the intensity of color as a physical experience. Kelly invites us to abandon narrative entirely and simply see.

Joan Miró – Sobreteixims i Escultures: The Tactility of Abstraction

Joan Miró’s late work often combined painting, collage, and tapestry, expanding the surface into a multi-dimensional field. In Sobreteixims i Escultures, the Catalan master blurs boundaries between two-dimensional and three-dimensional art.

The rough textures and playful forms exemplify Miró’s connection to Automatism—an approach aligned with Surrealism, where chance and subconscious gestures guide the work. When engaging with this piece, viewers might notice how the irregular surfaces demand not just visual but almost tactile attention, shifting abstraction into a sensory encounter.

Pierre Soulages – Eau-forte XXXII: Black as a World of Light

French painter Pierre Soulages devoted much of his life to exploring the depth of black, a practice he called Outrenoir—“beyond black.” In his etching Eau-forte XXXII, black is not the absence of color but a dynamic surface that interacts with light.

The etched lines cut through darkness, revealing luminosity within shadow. To appreciate Soulages’ abstraction is to slow down and notice subtleties: how black reflects, absorbs, or releases light depending on angle and surface.

Helen Frankenthaler – Solar Imp: The Lyrical Flow of Color

Helen Frankenthaler, a pioneer of Abstract Expressionism and the Color Field movement, developed the “soak-stain” technique, allowing pigment to seep into raw canvas. In Solar Imp, broad, translucent washes of color spread like atmospheric phenomena.

Unlike Kelly’s precise forms, Frankenthaler’s abstraction is fluid and intuitive. Approaching her work involves surrender—letting the eye wander across expanses of color, noting how they bleed, overlap, and create depth. Her paintings remind us that abstraction can be as much about mood as about form.

Robert Motherwell – Nocturne II (from the Octavio Paz Suite): Poetry in Abstraction

Robert Motherwell, another key figure in Abstract Expressionism, often combined gestural abstraction with literary and philosophical influences. Nocturne II was part of a suite inspired by Mexican poet Octavio Paz, bridging painting and poetry.

Here, dark, gestural forms move across the surface with gravity and rhythm. To decode such a work is not to translate it into words but to sense its resonance—how visual marks might echo the cadence of poetry or the weight of silence.

How to Approach Abstract Art as a Viewer

When faced with non-representational works, the key is to release the expectation of narrative. Instead, consider:

- Form and Composition: How do shapes relate? Where is the balance or imbalance?

- Color and Texture: What emotions do colors evoke? What role does surface play?

- Materiality and Process: How does the medium—steel, canvas, print, or digital—affect your perception?

- Movement and Rhythm: Does the work suggest stillness, dynamism, chaos, or harmony?

Equally important is to notice your own response. Abstraction often functions like music: it may not depict anything directly, but it can stir profound emotional and sensory reactions.

Conclusion: The Open Invitation of Abstraction

Abstract art resists singular interpretation, and that is precisely its power. Works by Chillida, Ruff, Calder, Kelly, Miró, Soulages, Frankenthaler, and Motherwell demonstrate the breadth of non-representational expression—from heavy steel to digital flux, from vibrant color fields to black etched depths.

To decode abstract art is less about solving a puzzle than about opening oneself to an encounter. Each viewer brings their own perspective, memory, and feeling to the work. The reward lies in embracing this openness: allowing abstraction to expand our ways of seeing and feeling, offering us not answers but experiences.