Francis Bacon: Distorted Realities and Raw Emotion

By Nana Japaridze

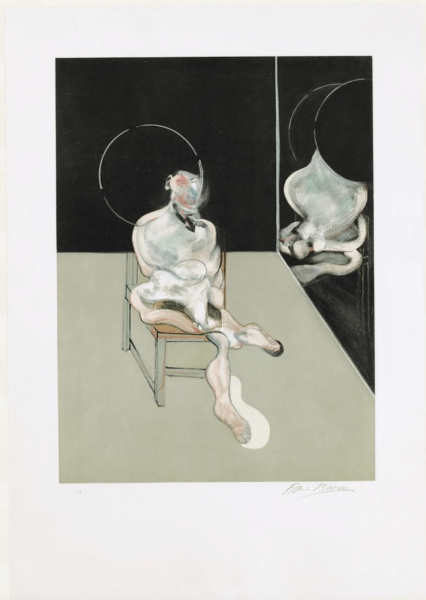

In a dimly lit London studio overflowing with paint-splattered chaos, Francis Bacon conjured nightmares onto canvas. The British-Irish painter became legendary for his distorted figures and raw emotional intensity—from screaming popes to twisted lovers. His canvases pulse with anguish and desire, their fleshy forms often resembling slabs of meat. Vulnerability, isolation, and mortality were his recurring themes, conveyed with an immediacy that bypassed intellect. Bacon once declared that a painting should hit the viewer’s nervous system directly, and his images do exactly that: they scream before they speak.

Wounded Humanity and Distorted Truth

Emerging from the ruins of World War II, Bacon captured the psychic wreckage of his age. Largely self-taught, he drew on Surrealism, photography, and the Old Masters to forge a fierce new language of figuration. In 1945, London audiences were stunned by Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion. Against a searing orange background, three grotesque, part-human creatures howl in torment. Critics described the work as “astonishingly sinister,” sensing in it the trauma of war and the newly revealed horrors of the concentration camps. With this painting, Bacon introduced a vision of humanity stripped bare, wounded, and unredeemed.

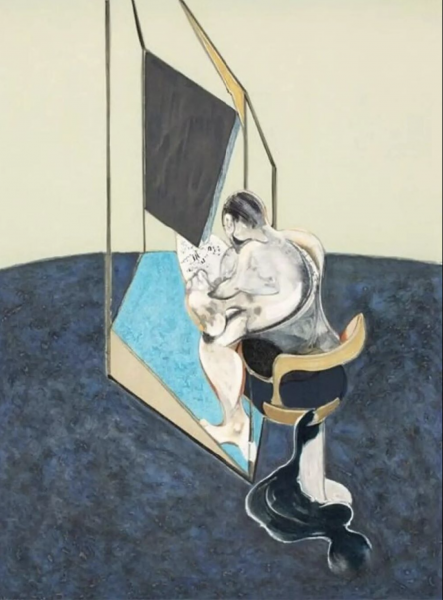

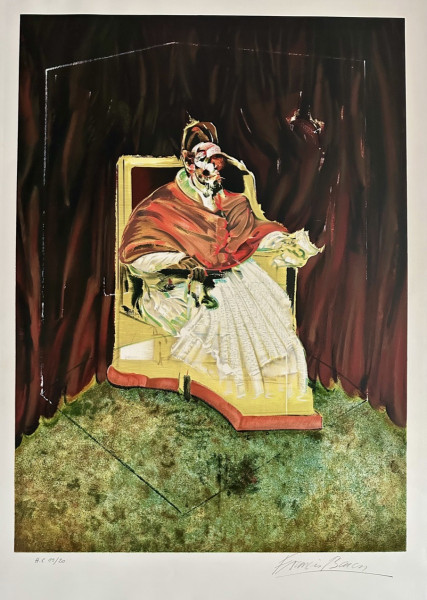

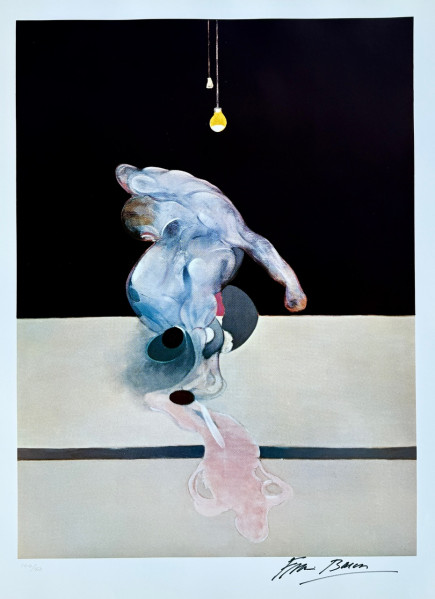

Through the following decades, he transformed figurative painting into something simultaneously human and horrific. His subjects—lonely figures trapped in geometric cages or shadowed rooms—seem suspended in psychological tension. He explored the body as a site of suffering and resilience, its contortions mirroring the mind’s turmoil. The Screaming Pope series epitomized his gift for transmuting tradition into terror: taking Velázquez’s stately Portrait of Pope Innocent X and reimagining it as a vision of existential despair. With slashing brushwork and dripping paint, Bacon turned papal grandeur into a study of fear and confinement. The effect was both horrifying and hypnotic, forcing postwar viewers to confront the fragility of the human spirit.

Despite their grotesque power, Bacon denied any desire merely to shock. His distortions, he said, aimed at revealing psychological truth—the essence of emotion beneath appearances. “My painting isn’t violent,” he insisted. “It’s life that is violent.” He sought to trap reality, to fix on canvas those fleeting sensations of dread, lust, or love that define existence. Working from photographs rather than live models allowed him to manipulate faces and bodies freely, bending them toward emotional truth rather than likeness. His repeated portraits of his lover George Dyer, for instance, smear beauty into tragedy—flesh dissolving into shadow, affection curdling into loss. Through distortion, Bacon exposed the tender violence of being alive.

The Soho Life: Art, Excess, and Despair

Bacon’s art was inseparable from his turbulent personal world. He lived between the extremes of luxury and ruin, of laughter and despair. A magnetic figure in postwar London’s bohemian scene, he was a founding member of Soho’s notorious Colony Room Club, where painters, poets, and gamblers drank late into the night. In that smoky upstairs bar, Bacon held court with champagne in hand, dazzling friends with darkly comic monologues. “We come from nothing and go into nothing,” he would proclaim, as if defying fate through wit. His nightlife fed his painting: the chaos, the drunken laughter, the raw encounters became part of his visual vocabulary.

Openly gay in a repressive era, Bacon embraced life’s excesses but carried their scars into his art. His relationships were intense, often destructive. In the 1950s he lived with Peter Lacy, a former fighter pilot whose volatile temper fueled both passion and pain. Later came George Dyer, a handsome petty criminal from London’s East End who became Bacon’s great love and tragic muse. Dyer’s insecurity and addiction led to constant turbulence, mirrored in the paintings that immortalized him. Bacon painted him over and over—sometimes tenderly, sometimes as a ghostly distortion, as if trying to hold onto him through paint.

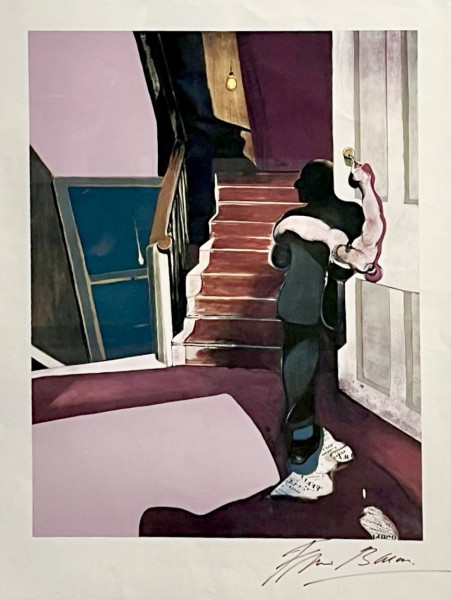

Tragedy struck in 1971, on the eve of Bacon’s grand retrospective at the Grand Palais in Paris. The night before the opening, Dyer took his own life in their hotel room. The exhibition, meant to crown Bacon’s career, became instead a requiem. The grief that followed poured into his Black Triptychs—three-panel paintings depicting Dyer’s final moments. Figures slump or fade into darkness; time seems suspended between life and death. Critics regard these works as some of Bacon’s greatest achievements, translating unbearable loss into visual poetry. The raw honesty of these triptychs confirmed Bacon as an artist unafraid to stare directly into suffering.

Legacy and Influence

By the time of his death in 1992, Bacon had cemented his place as one of the most powerful painters of the twentieth century. At a moment when abstraction dominated, he reaffirmed the vitality of the human figure—yet twisted it into new, unsettling forms. His art proved that figuration could be as radical as abstraction, that emotion could be conveyed through distortion as forcefully as through color or form.

Bacon’s influence echoes through generations of artists. Jenny Saville continues his exploration of flesh and vulnerability on monumental canvases; George Condo extends his psychological distortions into the absurd; Lucian Freud, Bacon’s friend and rival, shared his obsession with the raw truth of the body, though approached it through realism. Even Damien Hirst has acknowledged Bacon’s influence, admiring his fearless confrontation with mortality and the human condition. Bacon’s insistence that art must engage with life’s brutality rather than escape it resonates across contemporary practice.

From the Studio to the Market

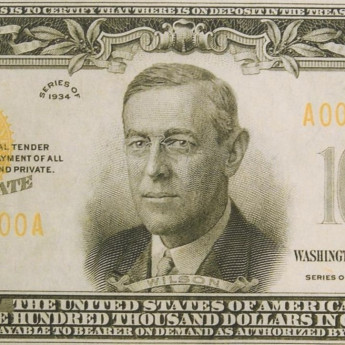

Bacon’s commitment to truth made him ruthless with his own work: he destroyed countless canvases that failed to meet his standards, leaving behind a finite body of paintings. This scarcity, combined with his enduring cultural weight, has made his works among the most coveted in the world. In 2013, his Three Studies of Lucian Freud sold for an astonishing $142.4 million, at the time the most expensive artwork ever auctioned. Yet beyond price tags, Bacon’s paintings command attention because they confront what most art avoids—the agony, desire, and transience of being human.

The Art of Distortion

Francis Bacon turned the human form inside out to reveal its hidden truths. His paintings are not merely scenes of horror but mirrors for our own anxieties and desires. In his distorted figures we recognize ourselves—our fragility, our longing, our fear of death. Bacon once said that within the grotesque there is beauty, and within beauty, horror. His canvases prove the point: they unsettle, move, and haunt long after one looks away.

Even decades after his death, Bacon’s work retains its electric force. The screams may have quieted, but their echo remains—reminding us that in distortion lies truth, and that the deepest art speaks not to reason but to the raw pulse of existence.

By Nana Japaridze

In a dimly lit London studio overflowing with paint-splattered chaos, Francis Bacon conjured nightmares onto canvas. The British-Irish painter became legendary for his distorted figures and raw emotional intensity—from screaming popes to twisted lovers. His canvases pulse with anguish and desire, their fleshy forms often resembling slabs of meat. Vulnerability, isolation, and mortality were his recurring themes, conveyed with an immediacy that bypassed intellect. Bacon once declared that a painting should hit the viewer’s nervous system directly, and his images do exactly that: they scream before they speak.

Wounded Humanity and Distorted Truth

Emerging from the ruins of World War II, Bacon captured the psychic wreckage of his age. Largely self-taught, he drew on Surrealism, photography, and the Old Masters to forge a fierce new language of figuration. In 1945, London audiences were stunned by Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion. Against a searing orange background, three grotesque, part-human creatures howl in torment. Critics described the work as “astonishingly sinister,” sensing in it the trauma of war and the newly revealed horrors of the concentration camps. With this painting, Bacon introduced a vision of humanity stripped bare, wounded, and unredeemed.

Through the following decades, he transformed figurative painting into something simultaneously human and horrific. His subjects—lonely figures trapped in geometric cages or shadowed rooms—seem suspended in psychological tension. He explored the body as a site of suffering and resilience, its contortions mirroring the mind’s turmoil. The Screaming Pope series epitomized his gift for transmuting tradition into terror: taking Velázquez’s stately Portrait of Pope Innocent X and reimagining it as a vision of existential despair. With slashing brushwork and dripping paint, Bacon turned papal grandeur into a study of fear and confinement. The effect was both horrifying and hypnotic, forcing postwar viewers to confront the fragility of the human spirit.

Despite their grotesque power, Bacon denied any desire merely to shock. His distortions, he said, aimed at revealing psychological truth—the essence of emotion beneath appearances. “My painting isn’t violent,” he insisted. “It’s life that is violent.” He sought to trap reality, to fix on canvas those fleeting sensations of dread, lust, or love that define existence. Working from photographs rather than live models allowed him to manipulate faces and bodies freely, bending them toward emotional truth rather than likeness. His repeated portraits of his lover George Dyer, for instance, smear beauty into tragedy—flesh dissolving into shadow, affection curdling into loss. Through distortion, Bacon exposed the tender violence of being alive.

The Soho Life: Art, Excess, and Despair

Bacon’s art was inseparable from his turbulent personal world. He lived between the extremes of luxury and ruin, of laughter and despair. A magnetic figure in postwar London’s bohemian scene, he was a founding member of Soho’s notorious Colony Room Club, where painters, poets, and gamblers drank late into the night. In that smoky upstairs bar, Bacon held court with champagne in hand, dazzling friends with darkly comic monologues. “We come from nothing and go into nothing,” he would proclaim, as if defying fate through wit. His nightlife fed his painting: the chaos, the drunken laughter, the raw encounters became part of his visual vocabulary.

Openly gay in a repressive era, Bacon embraced life’s excesses but carried their scars into his art. His relationships were intense, often destructive. In the 1950s he lived with Peter Lacy, a former fighter pilot whose volatile temper fueled both passion and pain. Later came George Dyer, a handsome petty criminal from London’s East End who became Bacon’s great love and tragic muse. Dyer’s insecurity and addiction led to constant turbulence, mirrored in the paintings that immortalized him. Bacon painted him over and over—sometimes tenderly, sometimes as a ghostly distortion, as if trying to hold onto him through paint.

Tragedy struck in 1971, on the eve of Bacon’s grand retrospective at the Grand Palais in Paris. The night before the opening, Dyer took his own life in their hotel room. The exhibition, meant to crown Bacon’s career, became instead a requiem. The grief that followed poured into his Black Triptychs—three-panel paintings depicting Dyer’s final moments. Figures slump or fade into darkness; time seems suspended between life and death. Critics regard these works as some of Bacon’s greatest achievements, translating unbearable loss into visual poetry. The raw honesty of these triptychs confirmed Bacon as an artist unafraid to stare directly into suffering.

Legacy and Influence

By the time of his death in 1992, Bacon had cemented his place as one of the most powerful painters of the twentieth century. At a moment when abstraction dominated, he reaffirmed the vitality of the human figure—yet twisted it into new, unsettling forms. His art proved that figuration could be as radical as abstraction, that emotion could be conveyed through distortion as forcefully as through color or form.

Bacon’s influence echoes through generations of artists. Jenny Saville continues his exploration of flesh and vulnerability on monumental canvases; George Condo extends his psychological distortions into the absurd; Lucian Freud, Bacon’s friend and rival, shared his obsession with the raw truth of the body, though approached it through realism. Even Damien Hirst has acknowledged Bacon’s influence, admiring his fearless confrontation with mortality and the human condition. Bacon’s insistence that art must engage with life’s brutality rather than escape it resonates across contemporary practice.

Bacon’s commitment to truth made him ruthless with his own work: he destroyed countless canvases that failed to meet his standards, leaving behind a finite body of paintings. This scarcity, combined with his enduring cultural weight, has made his works among the most coveted in the world. In 2013, his Three Studies of Lucian Freud sold for an astonishing $142.4 million, at the time the most expensive artwork ever auctioned. Yet beyond price tags, Bacon’s paintings command attention because they confront what most art avoids—the agony, desire, and transience of being human.

Francis Bacon turned the human form inside out to reveal its hidden truths. His paintings are not merely scenes of horror but mirrors for our own anxieties and desires. In his distorted figures we recognize ourselves—our fragility, our longing, our fear of death. Bacon once said that within the grotesque there is beauty, and within beauty, horror. His canvases prove the point: they unsettle, move, and haunt long after one looks away.

Even decades after his death, Bacon’s work retains its electric force. The screams may have quieted, but their echo remains—reminding us that in distortion lies truth, and that the deepest art speaks not to reason but to the raw pulse of existence.