Jean-Michel Basquiat: From Graffiti to Auction Superstar – A Deep Dive into Basquiat’s Journey

By Nana Japaridze

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s rise is one of the most remarkable stories in modern art. In the late 1970s, mysterious graffiti signed “SAMO©” began appearing across downtown New York. These cryptic phrases, sprayed onto SoHo walls and subway stations, caught the city’s creative scene by surprise. Behind them was a restless Brooklyn teenager—Basquiat himself—turning urban streets into his first gallery. Within a few short years, he went from tagging walls to painting monumental canvases that electrified the art world. By the 1980s, he was exhibiting internationally, socializing with Warhol and Madonna, and painting in Armani suits. Decades later, his 1982 skull painting would sell for an astonishing $110.5 million, making him the most expensive American artist ever sold at auction. His trajectory—from outsider graffiti poet to global art-market legend—explains why Basquiat remains one of the most coveted and essential figures in contemporary art.

Graffiti Roots and Meteoric Rise

Basquiat was born in Brooklyn in 1960 to a Haitian father and Puerto Rican mother. A precocious teen, he adopted the pseudonym SAMO©—short for “Same Old Crap”—to mock the stale ideas of mainstream society. Alongside his friend Al Diaz, he spray-painted witty, often biting slogans across Lower Manhattan: poetic fragments like “SAMO© as an end to mindwash religion, nowhere politics, and bogus philosophy.” These messages blurred street art and literary provocation, sparking intrigue among New York’s downtown scene.

By 1980, the SAMO© partnership ended, but Basquiat’s career was only beginning. He moved effortlessly from the streets into galleries, bringing with him a raw, unfiltered energy that captivated the avant-garde. That summer, at just 19, he participated in the Times Square Show, a scrappy but influential exhibition that launched many careers. His paintings—bold, improvisational, and unlike anything else—quickly drew critical and commercial attention. By 1982, he was exhibiting alongside Julian Schnabel and David Salle and became the youngest artist to participate in Documenta in Kassel, Germany. Critics hailed him as the most exciting new talent of his generation.

His ascent was meteoric, but not without tension. As a young Black artist in a mostly white art world, he faced both fetishization and racism. Some dismissed his work as “primitive,” ignoring its sophistication. Basquiat responded through his art, addressing race, power, and inequality with biting intelligence. He thrived in the creative ferment of 1980s New York, alongside peers like Keith Haring, Jeff Koons, and Kenny Scharf. His East Village studio became a hive of musicians, painters, and graffiti artists, reflecting a cultural scene that blurred boundaries between high art and subculture.

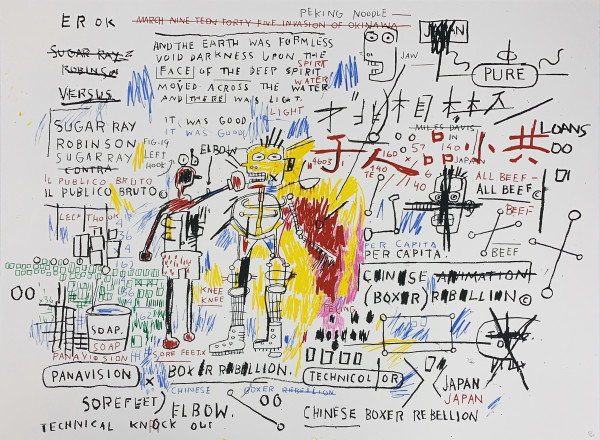

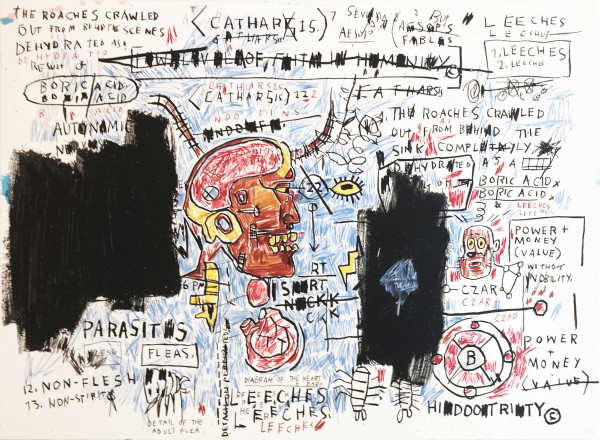

The Art of a Visionary: Heritage, Jazz, and the Crown

Basquiat was largely self-taught, but his paintings possessed a complexity that came from a unique fusion of sources. He once said his art should “hit the mind like jazz,” and indeed music was central to his work. He adored bebop legends like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, often painting to jazz or hip-hop blasting in the background. His 1983 painting Horn Players is a visual riff on jazz improvisation, filled with fragmented text, skeletal figures, and rhythmic marks that feel as spontaneous as a saxophone solo.

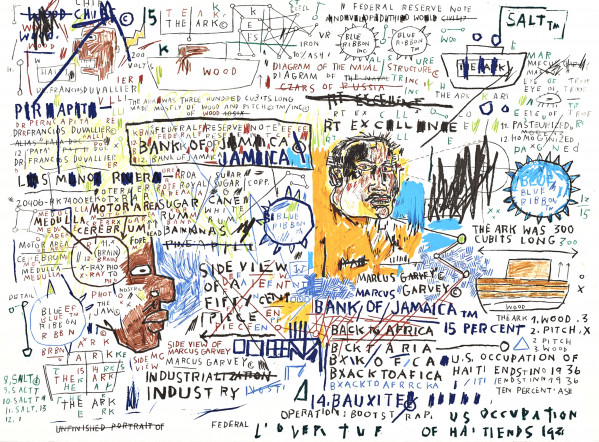

Equally vital was his cultural heritage. As a Black and Puerto Rican artist in an overwhelmingly white establishment, Basquiat deliberately celebrated Black history and heroes in his paintings. He listed names of jazz musicians, athletes, and activists directly onto his canvases, honoring figures like Parker, Muhammad Ali, Marcus Garvey, and Malcolm X. His paintings are palimpsests of identity—layers of historical references, personal symbols, and contemporary critique. He refused to let Black figures be sidelined; instead, he crowned them.

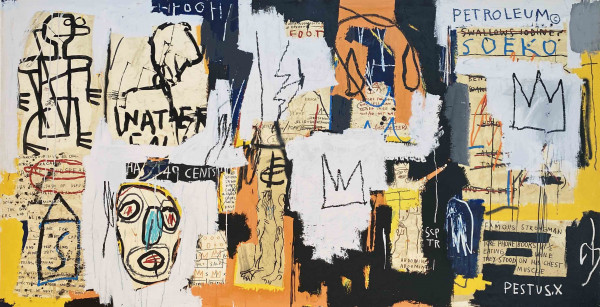

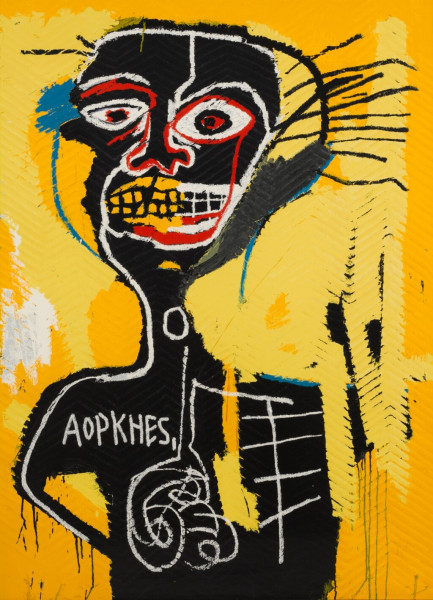

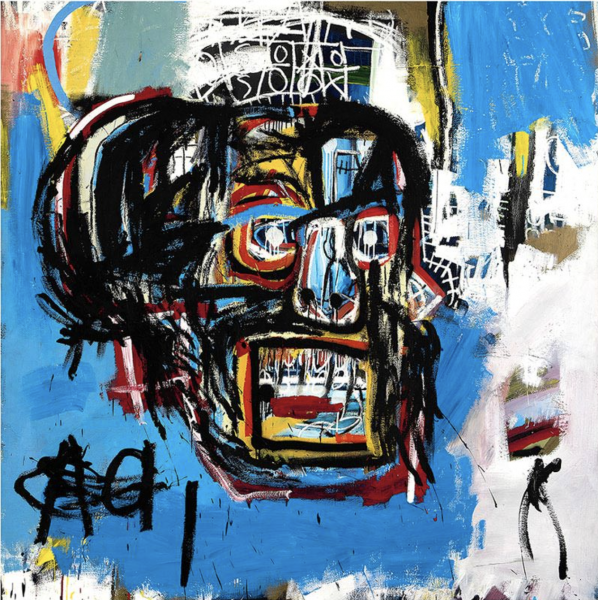

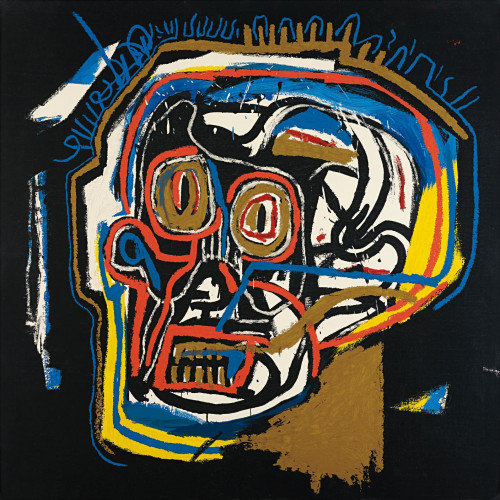

The crown motif is one of Basquiat’s most iconic symbols. A simple three-pointed crown appears throughout his oeuvre, scrawled above the heads of his heroes. It served as both signature and statement: a way of declaring Black excellence and challenging the hierarchies of Western art history. The crown echoed medieval halos but redirected reverence toward boxers, jazz musicians, and Black visionaries who had been overlooked by the canon. Alongside crowns, skeletal forms and anatomical drawings (inspired by a childhood fascination with Gray’s Anatomy) gave his paintings a visceral immediacy. His art was a language unto itself—poetic, furious, celebratory, and deeply alive.

Warhol, Friendship, and the 1980s Scene

Basquiat emerged during a vibrant moment in New York’s cultural history. He became close friends with Keith Haring, bonding over shared street art roots, and immersed himself in the downtown nightlife at places like CBGB and the Mudd Club. He played in a noise band, collaborated with fellow artists, and moved between uptown elites and gritty downtown bohemia with ease.

The most transformative relationship of his career was with Andy Warhol. They first crossed paths in 1979 when Basquiat, then unknown, boldly approached Warhol in a restaurant to sell him a postcard. A few years later, they were formally introduced by art dealer Bruno Bischofberger, and a dynamic friendship began. Warhol admired Basquiat’s raw energy; Basquiat revered Warhol’s cultural savvy. From 1984 onward, they collaborated on around 160 paintings, layering Warhol’s silkscreened logos with Basquiat’s expressive brushwork and graffiti. Works like Olympic Rings and Arm and Hammer II merged pop iconography with Basquiat’s personal symbolism, creating a dialogue between two artistic generations.

Their friendship went beyond the canvas. Warhol provided Basquiat with studio space and mentorship, while the pair became fixtures of the New York scene—an unlikely duo: the peroxide-haired Pop icon and the dreadlocked prodigy. In 1985, their joint exhibition was promoted with a poster depicting them as boxers, playfully acknowledging their star power. Critics were divided, but the collaboration remains one of the most fascinating chapters in late 20th-century art.

Fame, Excess, and Tragedy

By the mid-1980s, Basquiat was living at dizzying speed. He was wealthy, famous, and constantly in demand. His paintings sold rapidly, he traveled for exhibitions, and he appeared on the cover of The New York Times Magazine as the face of the new art scene. Yet success brought pressure and isolation. He felt the weight of being tokenized, once scrawling “Famous Negro Athlete” in a painting to mock the art world’s treatment of him. Drug use, once recreational, became a dependency.

The death of Andy Warhol in 1987 was a devastating blow. Warhol’s friendship had been a stabilizing force; without him, Basquiat felt unmoored. His heroin use escalated, his behavior became erratic, and he increasingly withdrew. On August 12, 1988, at just 27 years old, Basquiat died of a heroin overdose in his East Village studio. His sudden death shocked the cultural world. As Keith Haring wrote, “He truly created a lifetime of work in ten years… he has left us a large treasure.” Basquiat’s meteoric rise and tragic end only deepened his mythic status, placing him alongside other brilliant talents lost too young.

Posthumous Legacy: Cultural Icon and Market Titan

Basquiat’s legacy has only grown since his death. Retrospectives around the world have cemented his place in art history, and younger generations continue to discover his work anew. He has become a cultural icon—his imagery reproduced on clothing, referenced in songs, and revered by musicians and fashion designers. Rappers like Jay-Z and Beyoncé collect his paintings, and Jay-Z famously rapped “I’m the new Jean-Michel” in 2013. Brands like Uniqlo and Reebok have licensed his imagery, bringing his rebellious aesthetic to mass audiences. Street artist Banksy has paid homage to Basquiat in public murals, acknowledging his foundational influence on contemporary street art.

Financially, Basquiat’s market has reached stratospheric heights. His 1982 skull painting, bought for $19,000 in the 1980s, sold at Sotheby’s in 2017 for $110.5 million to Japanese collector Yusaku Maezawa—a record price for an American artist. Basquiat became the youngest artist to join the $100 million club, surpassing even Picasso’s record. His works are now centerpieces in major collections from MoMA to the Broad, and their scarcity combined with cultural significance keeps demand extraordinarily high.

Why Basquiat Endures

Basquiat’s importance lies not just in his market value but in the revolutionary force of his art. He bridged the gap between street culture and high art, challenged racial narratives in museums, and developed a visual language that remains as urgent today as it was in the 1980s. His paintings teem with emotion—wild colors, scrawled words, crowned heroes—and they speak to issues of identity, injustice, and creativity with a clarity that resonates across generations.

He once said, “I’m not a real person. I’m a legend.” And indeed, the legend lives on. From New York’s concrete walls to the world’s most prestigious auction houses, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s journey is a story of raw talent, cultural defiance, and lasting influence. His crown still shines brightly—an emblem of genius that came from the margins and changed the art world forever.

By Nana Japaridze

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s rise is one of the most remarkable stories in modern art. In the late 1970s, mysterious graffiti signed “SAMO©” began appearing across downtown New York. These cryptic phrases, sprayed onto SoHo walls and subway stations, caught the city’s creative scene by surprise. Behind them was a restless Brooklyn teenager—Basquiat himself—turning urban streets into his first gallery. Within a few short years, he went from tagging walls to painting monumental canvases that electrified the art world. By the 1980s, he was exhibiting internationally, socializing with Warhol and Madonna, and painting in Armani suits. Decades later, his 1982 skull painting would sell for an astonishing $110.5 million, making him the most expensive American artist ever sold at auction. His trajectory—from outsider graffiti poet to global art-market legend—explains why Basquiat remains one of the most coveted and essential figures in contemporary art.

Graffiti Roots and Meteoric Rise

Basquiat was born in Brooklyn in 1960 to a Haitian father and Puerto Rican mother. A precocious teen, he adopted the pseudonym SAMO©—short for “Same Old Crap”—to mock the stale ideas of mainstream society. Alongside his friend Al Diaz, he spray-painted witty, often biting slogans across Lower Manhattan: poetic fragments like “SAMO© as an end to mindwash religion, nowhere politics, and bogus philosophy.” These messages blurred street art and literary provocation, sparking intrigue among New York’s downtown scene.

By 1980, the SAMO© partnership ended, but Basquiat’s career was only beginning. He moved effortlessly from the streets into galleries, bringing with him a raw, unfiltered energy that captivated the avant-garde. That summer, at just 19, he participated in the Times Square Show, a scrappy but influential exhibition that launched many careers. His paintings—bold, improvisational, and unlike anything else—quickly drew critical and commercial attention. By 1982, he was exhibiting alongside Julian Schnabel and David Salle and became the youngest artist to participate in Documenta in Kassel, Germany. Critics hailed him as the most exciting new talent of his generation.

His ascent was meteoric, but not without tension. As a young Black artist in a mostly white art world, he faced both fetishization and racism. Some dismissed his work as “primitive,” ignoring its sophistication. Basquiat responded through his art, addressing race, power, and inequality with biting intelligence. He thrived in the creative ferment of 1980s New York, alongside peers like Keith Haring, Jeff Koons, and Kenny Scharf. His East Village studio became a hive of musicians, painters, and graffiti artists, reflecting a cultural scene that blurred boundaries between high art and subculture.

The Art of a Visionary: Heritage, Jazz, and the Crown

Basquiat was largely self-taught, but his paintings possessed a complexity that came from a unique fusion of sources. He once said his art should “hit the mind like jazz,” and indeed music was central to his work. He adored bebop legends like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, often painting to jazz or hip-hop blasting in the background. His 1983 painting Horn Players is a visual riff on jazz improvisation, filled with fragmented text, skeletal figures, and rhythmic marks that feel as spontaneous as a saxophone solo.

Equally vital was his cultural heritage. As a Black and Puerto Rican artist in an overwhelmingly white establishment, Basquiat deliberately celebrated Black history and heroes in his paintings. He listed names of jazz musicians, athletes, and activists directly onto his canvases, honoring figures like Parker, Muhammad Ali, Marcus Garvey, and Malcolm X. His paintings are palimpsests of identity—layers of historical references, personal symbols, and contemporary critique. He refused to let Black figures be sidelined; instead, he crowned them.

The crown motif is one of Basquiat’s most iconic symbols. A simple three-pointed crown appears throughout his oeuvre, scrawled above the heads of his heroes. It served as both signature and statement: a way of declaring Black excellence and challenging the hierarchies of Western art history. The crown echoed medieval halos but redirected reverence toward boxers, jazz musicians, and Black visionaries who had been overlooked by the canon. Alongside crowns, skeletal forms and anatomical drawings (inspired by a childhood fascination with Gray’s Anatomy) gave his paintings a visceral immediacy. His art was a language unto itself—poetic, furious, celebratory, and deeply alive.

Warhol, Friendship, and the 1980s Scene

Basquiat emerged during a vibrant moment in New York’s cultural history. He became close friends with Keith Haring, bonding over shared street art roots, and immersed himself in the downtown nightlife at places like CBGB and the Mudd Club. He played in a noise band, collaborated with fellow artists, and moved between uptown elites and gritty downtown bohemia with ease.

The most transformative relationship of his career was with Andy Warhol. They first crossed paths in 1979 when Basquiat, then unknown, boldly approached Warhol in a restaurant to sell him a postcard. A few years later, they were formally introduced by art dealer Bruno Bischofberger, and a dynamic friendship began. Warhol admired Basquiat’s raw energy; Basquiat revered Warhol’s cultural savvy. From 1984 onward, they collaborated on around 160 paintings, layering Warhol’s silkscreened logos with Basquiat’s expressive brushwork and graffiti. Works like Olympic Rings and Arm and Hammer II merged pop iconography with Basquiat’s personal symbolism, creating a dialogue between two artistic generations.

Their friendship went beyond the canvas. Warhol provided Basquiat with studio space and mentorship, while the pair became fixtures of the New York scene—an unlikely duo: the peroxide-haired Pop icon and the dreadlocked prodigy. In 1985, their joint exhibition was promoted with a poster depicting them as boxers, playfully acknowledging their star power. Critics were divided, but the collaboration remains one of the most fascinating chapters in late 20th-century art.

Fame, Excess, and Tragedy

By the mid-1980s, Basquiat was living at dizzying speed. He was wealthy, famous, and constantly in demand. His paintings sold rapidly, he traveled for exhibitions, and he appeared on the cover of The New York Times Magazine as the face of the new art scene. Yet success brought pressure and isolation. He felt the weight of being tokenized, once scrawling “Famous Negro Athlete” in a painting to mock the art world’s treatment of him. Drug use, once recreational, became a dependency.

The death of Andy Warhol in 1987 was a devastating blow. Warhol’s friendship had been a stabilizing force; without him, Basquiat felt unmoored. His heroin use escalated, his behavior became erratic, and he increasingly withdrew. On August 12, 1988, at just 27 years old, Basquiat died of a heroin overdose in his East Village studio. His sudden death shocked the cultural world. As Keith Haring wrote, “He truly created a lifetime of work in ten years… he has left us a large treasure.” Basquiat’s meteoric rise and tragic end only deepened his mythic status, placing him alongside other brilliant talents lost too young.

Posthumous Legacy: Cultural Icon and Market Titan

Basquiat’s legacy has only grown since his death. Retrospectives around the world have cemented his place in art history, and younger generations continue to discover his work anew. He has become a cultural icon—his imagery reproduced on clothing, referenced in songs, and revered by musicians and fashion designers. Rappers like Jay-Z and Beyoncé collect his paintings, and Jay-Z famously rapped “I’m the new Jean-Michel” in 2013. Brands like Uniqlo and Reebok have licensed his imagery, bringing his rebellious aesthetic to mass audiences. Street artist Banksy has paid homage to Basquiat in public murals, acknowledging his foundational influence on contemporary street art.

Financially, Basquiat’s market has reached stratospheric heights. His 1982 skull painting, bought for $19,000 in the 1980s, sold at Sotheby’s in 2017 for $110.5 million to Japanese collector Yusaku Maezawa—a record price for an American artist. Basquiat became the youngest artist to join the $100 million club, surpassing even Picasso’s record. His works are now centerpieces in major collections from MoMA to the Broad, and their scarcity combined with cultural significance keeps demand extraordinarily high.

Why Basquiat Endures

Basquiat’s importance lies not just in his market value but in the revolutionary force of his art. He bridged the gap between street culture and high art, challenged racial narratives in museums, and developed a visual language that remains as urgent today as it was in the 1980s. His paintings teem with emotion—wild colors, scrawled words, crowned heroes—and they speak to issues of identity, injustice, and creativity with a clarity that resonates across generations.

He once said, “I’m not a real person. I’m a legend.” And indeed, the legend lives on. From New York’s concrete walls to the world’s most prestigious auction houses, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s journey is a story of raw talent, cultural defiance, and lasting influence. His crown still shines brightly—an emblem of genius that came from the margins and changed the art world forever.