Tracey Emin: Confessional Art on Display

By Emilia Novak

Few contemporary artists have blurred the line between private life and public exhibition as daringly as Tracey Emin. Her art is not merely autobiographical — it is confessional, vulnerable, and often startlingly intimate. Over the past three decades, Emin has transformed the raw material of her personal experiences into some of the most talked-about artworks in Britain, earning both scorn and admiration in equal measure. Where many artists construct narratives at a distance, Emin simply opens the door and invites us straight into her world — heartbreak, chaos, longing, and all.

From Margate to the Art World’s Spotlight

Tracey Emin was born in 1963 in the seaside town of Margate, England. Her early life was turbulent: her father owned a hotel that later fell into decline, and she endured significant personal trauma, including sexual assault as a teenager. These experiences shaped her worldview and later became the foundation for her unfiltered artistic voice.

Emin studied at Maidstone College of Art and later at London’s Royal College of Art, graduating in 1989 with a degree in painting. But the transition into professional artmaking wasn’t smooth. In a fit of despair, she famously destroyed most of her early paintings, declaring that she would never paint again. What emerged from those ashes was an artist determined to confront her life head-on, using whatever medium could best express her inner landscape — whether that was embroidery, found objects, neon lights, or video confessionals.

By the early 1990s, Emin had become part of the circle that would soon be labeled the Young British Artists (YBAs) — a group that included Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas, and Marc Quinn. Backed by collector Charles Saatchi, the YBAs were brash, media-savvy, and eager to shock Britain’s conservative art establishment. Yet while some relied on provocative materials (Hirst’s formaldehyde shark, Quinn’s blood sculpture), Emin’s radicalism lay elsewhere: in radical honesty.

She once said, “There should be something revelatory about art… it should be totally creative and open doors for new thoughts and experiences.” Her revelation was herself.

The Tent: Turning Memory into Monument

In 1995, Emin produced a work that would define her confessional style:

Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995.

This installation consisted of a small camping tent, lit from within, its interior carefully appliquéd with 102 names. They ranged from lovers and close friends to family members — even the unborn twins Emin miscarried. At first glance, the title sounds salacious, even sensational. But stepping inside reveals something far more tender. The tent is a kind of fabric diary, a monument to shared moments of intimacy, whether sexual, familial, or simply emotional.

On the floor of the tent, Emin stitched the words “With myself, always myself, never forgetting.” This quiet declaration of memory and self-reflection framed the piece as an act of personal archiving. Here was a young woman artist laying out the fabric of her life, quite literally, for public view.

The piece caused a sensation. Critics and viewers alike were divided between those who dismissed it as crude exhibitionism and those who recognized its emotional power. Today, it’s remembered as a landmark work that announced Emin as a new kind of artist: one who used confession as both subject and medium.

Sadly, the tent was destroyed in a 2004 warehouse fire that consumed part of the Saatchi collection. Its loss was felt widely — a bitter irony given that the work had once been derided by tabloids and is now seen as an irreplaceable cultural artifact.

My Bed: Scandal, Vulnerability, Connection

If the tent marked her arrival, My Bed (1998) made her a household name. For the Turner Prize exhibition at Tate Gallery in 1999, Emin presented her actual unmade bed, surrounded by the remnants of a deep depressive episode. Strewn across the floor were empty vodka bottles, cigarette packets, condoms, used tissues, underwear, and other personal detritus. She had spent several days confined to that bed after a painful breakup, and upon finally standing, decided that the aftermath itself told a story worth sharing.

The reaction was immediate and intense. The tabloids erupted in outrage. Critics accused her of narcissism and attention-seeking. One famously called the work “endlessly solipsistic,” branding Emin a bore rather than a visionary. Yet the public response proved more complex.

For many visitors, the installation resonated on a profoundly emotional level. Tate curators described the scene as resembling a “crime scene of a broken heart,” inviting viewers to examine the evidence of pain. Beneath the shock factor was something raw and universal: heartbreak, loneliness, shame, vulnerability. Emin had taken the stuff people hide away and placed it in a museum, turning private despair into public art.

The work also sparked one of the more surreal moments in recent British art history. Two performance artists, Yuan Chai and Jian Jun Xi, staged a semi-naked pillow fight on the bed while it was on display. Security swiftly intervened, but the incident — which Emin later dubbed “The Battle of the Bed” — only cemented the work’s fame. It had become so iconic that it inspired its own spin-off performances.

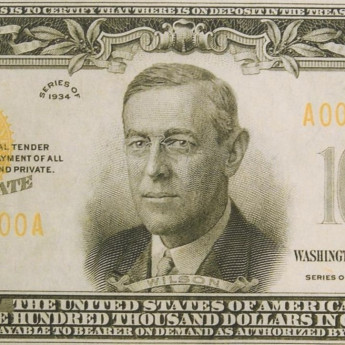

When My Bed sold at Christie’s London in 2014 for £2.54 million, more than double its estimate, it confirmed Emin’s place in the canon of contemporary art. Saatchi had purchased it for £150,000 in 2000; in just over a decade, its value had multiplied seventeen-fold.

Neon Confessions: Writing in Light

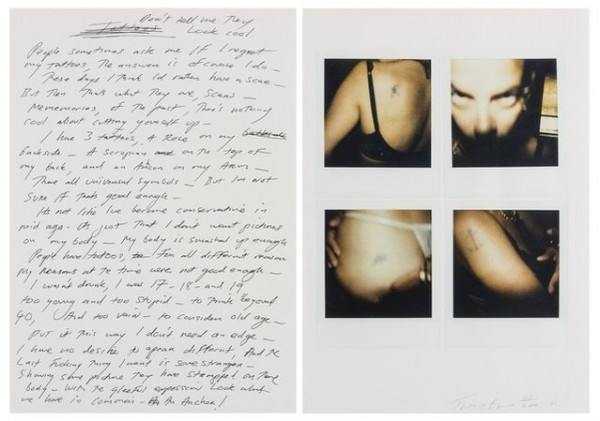

In the mid-1990s, Emin began experimenting with neon light installations, which would become one of her most recognizable mediums. She transformed her handwritten notes, love letters, and confessions into glowing wall pieces.

Phrases like:

- “You Forgot to Kiss My Soul”

- “I Promise To Love You”

- “Meet Me in Heaven I Will Wait for You”

…glow in her looping, unmistakable handwriting. By using neon, a commercial medium associated with funfairs and shopfronts, Emin juxtaposed the nostalgic warmth of light with often painful or yearning messages. Growing up in Margate, she was surrounded by neon signs on the seafront; this aesthetic shaped her visual language.

She once remarked, “Neon is emotional for everybody… it’s a feel-good factor.” That warmth makes her personal phrases strangely universal. People see their own feelings reflected in those glowing lines, which is why her neon pieces have become coveted by collectors and museums worldwide.

Painting, Drawing, and Returning to the Body

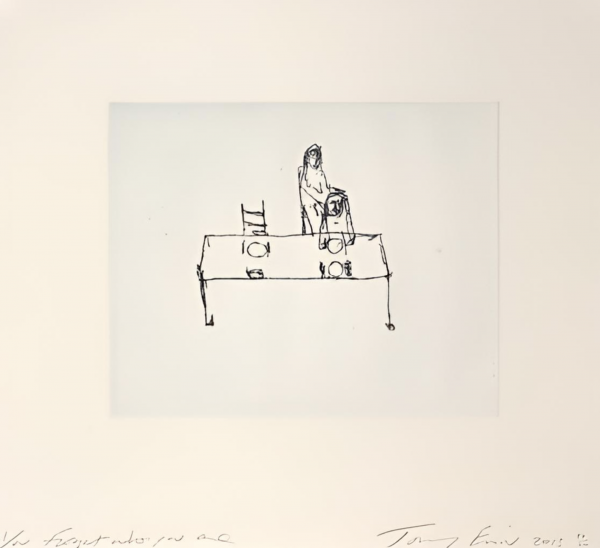

Although she rejected painting early in her career, Emin eventually returned to it in the 2000s and 2010s. Her paintings and drawings explore female desire, loneliness, and vulnerability through expressive, gestural brushwork. Influences from Edvard Munch and Egon Schiele are clear: both artists famously laid their emotional lives bare through intense self-representation.

Emin’s return to these traditional mediums marked a kind of maturation, but not a softening. Her canvases remain confessional, often featuring solitary female figures, raw lines, and urgent scrawled phrases. They are less sensational than her installations, but just as personal — like diary entries rendered in paint.

She also expanded into sculpture, notably with The Mother (2022), a nine-metre bronze figure permanently installed outside the MUNCH Museum in Oslo. Depicting a nude woman kneeling protectively, it is dedicated to “all mothers and women” and to Munch’s own mother. This work reflects Emin’s deep admiration for Munch, whose emotional honesty profoundly influenced her. It also speaks to her own complex feelings about motherhood, having never had children.

The Mother marked a shift: the once-rebellious YBA was now producing monumental public artworks — yet still rooted in autobiography.

From Controversy to Cultural Dame

Over time, Emin’s status transformed dramatically. The enfant terrible of the 1990s became a respected figure of the British art establishment. She was made a Royal Academician in 2007, awarded a CBE in 2013, and in 2024 received the title of Dame Commander (DBE) for her contributions to art.

Personal challenges also shaped her later work. In 2020, she was diagnosed with cancer and underwent extensive surgery. She has spoken openly about this experience, creating self-portraits that grapple with mortality and survival. Her work remains fiercely personal, proving that the confessional mode isn’t a youthful gimmick — it’s her lifelong language.

Why Collectors Care

For collectors, Emin occupies a unique position. Her works are deeply personal yet widely resonant; they’re not just objects, but fragments of a lived life. In a market often dominated by conceptual distance, Emin offers authenticity.

Owning an Emin means owning a story — whether that’s the glowing intimacy of a neon sign, a vulnerable drawing, or a historically significant installation. Her works consistently command strong auction results, but their true value lies in their emotional power. Collectors often describe a sense of recognition when living with her art, as if it articulates something they themselves have felt but never expressed.

Even works that no longer exist, like the destroyed tent, have become cultural touchstones. The public once mocked the piece; after its loss, they mourned it. This reversal speaks volumes about Emin’s impact. She has reshaped how we think about autobiography in art — not as indulgence, but as connection.

A Lasting Legacy

Tracey Emin once remarked, “It’s important that my work is about me and my experiences. If it wasn’t, it would be dishonest.”

This uncompromising stance has defined her entire career. What was once dismissed as confessional oversharing is now celebrated for its honesty, vulnerability, and emotional depth. Like Frida Kahlo or Louise Bourgeois, Emin has turned personal history into universally resonant symbols.

For viewers, her art is a mirror: sometimes uncomfortable, sometimes illuminating, but always real. For collectors, it’s an opportunity to own a piece of cultural history — art that doesn’t just decorate a wall but starts conversations, challenges taboos, and connects on a human level.

Tracey Emin opened the door to her life, and in doing so, opened a door for us to see ourselves more clearly. Her confessional art invites us not just to look, but to feel. And that may be why her legacy, like the glowing lines of her neon signs, continues to shine brightly in the landscape of contemporary art.

By Emilia Novak

Few contemporary artists have blurred the line between private life and public exhibition as daringly as Tracey Emin. Her art is not merely autobiographical — it is confessional, vulnerable, and often startlingly intimate. Over the past three decades, Emin has transformed the raw material of her personal experiences into some of the most talked-about artworks in Britain, earning both scorn and admiration in equal measure. Where many artists construct narratives at a distance, Emin simply opens the door and invites us straight into her world — heartbreak, chaos, longing, and all.

From Margate to the Art World’s Spotlight

Tracey Emin was born in 1963 in the seaside town of Margate, England. Her early life was turbulent: her father owned a hotel that later fell into decline, and she endured significant personal trauma, including sexual assault as a teenager. These experiences shaped her worldview and later became the foundation for her unfiltered artistic voice.

Emin studied at Maidstone College of Art and later at London’s Royal College of Art, graduating in 1989 with a degree in painting. But the transition into professional artmaking wasn’t smooth. In a fit of despair, she famously destroyed most of her early paintings, declaring that she would never paint again. What emerged from those ashes was an artist determined to confront her life head-on, using whatever medium could best express her inner landscape — whether that was embroidery, found objects, neon lights, or video confessionals.

By the early 1990s, Emin had become part of the circle that would soon be labeled the Young British Artists (YBAs) — a group that included Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas, and Marc Quinn. Backed by collector Charles Saatchi, the YBAs were brash, media-savvy, and eager to shock Britain’s conservative art establishment. Yet while some relied on provocative materials (Hirst’s formaldehyde shark, Quinn’s blood sculpture), Emin’s radicalism lay elsewhere: in radical honesty.

She once said, “There should be something revelatory about art… it should be totally creative and open doors for new thoughts and experiences.” Her revelation was herself.

The Tent: Turning Memory into Monument

In 1995, Emin produced a work that would define her confessional style:

Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995.

This installation consisted of a small camping tent, lit from within, its interior carefully appliquéd with 102 names. They ranged from lovers and close friends to family members — even the unborn twins Emin miscarried. At first glance, the title sounds salacious, even sensational. But stepping inside reveals something far more tender. The tent is a kind of fabric diary, a monument to shared moments of intimacy, whether sexual, familial, or simply emotional.

On the floor of the tent, Emin stitched the words “With myself, always myself, never forgetting.” This quiet declaration of memory and self-reflection framed the piece as an act of personal archiving. Here was a young woman artist laying out the fabric of her life, quite literally, for public view.

The piece caused a sensation. Critics and viewers alike were divided between those who dismissed it as crude exhibitionism and those who recognized its emotional power. Today, it’s remembered as a landmark work that announced Emin as a new kind of artist: one who used confession as both subject and medium.

Sadly, the tent was destroyed in a 2004 warehouse fire that consumed part of the Saatchi collection. Its loss was felt widely — a bitter irony given that the work had once been derided by tabloids and is now seen as an irreplaceable cultural artifact.

My Bed: Scandal, Vulnerability, Connection

If the tent marked her arrival, My Bed (1998) made her a household name. For the Turner Prize exhibition at Tate Gallery in 1999, Emin presented her actual unmade bed, surrounded by the remnants of a deep depressive episode. Strewn across the floor were empty vodka bottles, cigarette packets, condoms, used tissues, underwear, and other personal detritus. She had spent several days confined to that bed after a painful breakup, and upon finally standing, decided that the aftermath itself told a story worth sharing.

The reaction was immediate and intense. The tabloids erupted in outrage. Critics accused her of narcissism and attention-seeking. One famously called the work “endlessly solipsistic,” branding Emin a bore rather than a visionary. Yet the public response proved more complex.

For many visitors, the installation resonated on a profoundly emotional level. Tate curators described the scene as resembling a “crime scene of a broken heart,” inviting viewers to examine the evidence of pain. Beneath the shock factor was something raw and universal: heartbreak, loneliness, shame, vulnerability. Emin had taken the stuff people hide away and placed it in a museum, turning private despair into public art.

The work also sparked one of the more surreal moments in recent British art history. Two performance artists, Yuan Chai and Jian Jun Xi, staged a semi-naked pillow fight on the bed while it was on display. Security swiftly intervened, but the incident — which Emin later dubbed “The Battle of the Bed” — only cemented the work’s fame. It had become so iconic that it inspired its own spin-off performances.

When My Bed sold at Christie’s London in 2014 for £2.54 million, more than double its estimate, it confirmed Emin’s place in the canon of contemporary art. Saatchi had purchased it for £150,000 in 2000; in just over a decade, its value had multiplied seventeen-fold.

Neon Confessions: Writing in Light

In the mid-1990s, Emin began experimenting with neon light installations, which would become one of her most recognizable mediums. She transformed her handwritten notes, love letters, and confessions into glowing wall pieces.

Phrases like:

- “You Forgot to Kiss My Soul”

- “I Promise To Love You”

- “Meet Me in Heaven I Will Wait for You”

…glow in her looping, unmistakable handwriting. By using neon, a commercial medium associated with funfairs and shopfronts, Emin juxtaposed the nostalgic warmth of light with often painful or yearning messages. Growing up in Margate, she was surrounded by neon signs on the seafront; this aesthetic shaped her visual language.

She once remarked, “Neon is emotional for everybody… it’s a feel-good factor.” That warmth makes her personal phrases strangely universal. People see their own feelings reflected in those glowing lines, which is why her neon pieces have become coveted by collectors and museums worldwide.

Painting, Drawing, and Returning to the Body

Although she rejected painting early in her career, Emin eventually returned to it in the 2000s and 2010s. Her paintings and drawings explore female desire, loneliness, and vulnerability through expressive, gestural brushwork. Influences from Edvard Munch and Egon Schiele are clear: both artists famously laid their emotional lives bare through intense self-representation.

Emin’s return to these traditional mediums marked a kind of maturation, but not a softening. Her canvases remain confessional, often featuring solitary female figures, raw lines, and urgent scrawled phrases. They are less sensational than her installations, but just as personal — like diary entries rendered in paint.

She also expanded into sculpture, notably with The Mother (2022), a nine-metre bronze figure permanently installed outside the MUNCH Museum in Oslo. Depicting a nude woman kneeling protectively, it is dedicated to “all mothers and women” and to Munch’s own mother. This work reflects Emin’s deep admiration for Munch, whose emotional honesty profoundly influenced her. It also speaks to her own complex feelings about motherhood, having never had children.

The Mother marked a shift: the once-rebellious YBA was now producing monumental public artworks — yet still rooted in autobiography.

From Controversy to Cultural Dame

Over time, Emin’s status transformed dramatically. The enfant terrible of the 1990s became a respected figure of the British art establishment. She was made a Royal Academician in 2007, awarded a CBE in 2013, and in 2024 received the title of Dame Commander (DBE) for her contributions to art.

Personal challenges also shaped her later work. In 2020, she was diagnosed with cancer and underwent extensive surgery. She has spoken openly about this experience, creating self-portraits that grapple with mortality and survival. Her work remains fiercely personal, proving that the confessional mode isn’t a youthful gimmick — it’s her lifelong language.

Why Collectors Care

For collectors, Emin occupies a unique position. Her works are deeply personal yet widely resonant; they’re not just objects, but fragments of a lived life. In a market often dominated by conceptual distance, Emin offers authenticity.

Owning an Emin means owning a story — whether that’s the glowing intimacy of a neon sign, a vulnerable drawing, or a historically significant installation. Her works consistently command strong auction results, but their true value lies in their emotional power. Collectors often describe a sense of recognition when living with her art, as if it articulates something they themselves have felt but never expressed.

Even works that no longer exist, like the destroyed tent, have become cultural touchstones. The public once mocked the piece; after its loss, they mourned it. This reversal speaks volumes about Emin’s impact. She has reshaped how we think about autobiography in art — not as indulgence, but as connection.

A Lasting Legacy

Tracey Emin once remarked, “It’s important that my work is about me and my experiences. If it wasn’t, it would be dishonest.”

This uncompromising stance has defined her entire career. What was once dismissed as confessional oversharing is now celebrated for its honesty, vulnerability, and emotional depth. Like Frida Kahlo or Louise Bourgeois, Emin has turned personal history into universally resonant symbols.

For viewers, her art is a mirror: sometimes uncomfortable, sometimes illuminating, but always real. For collectors, it’s an opportunity to own a piece of cultural history — art that doesn’t just decorate a wall but starts conversations, challenges taboos, and connects on a human level.

Tracey Emin opened the door to her life, and in doing so, opened a door for us to see ourselves more clearly. Her confessional art invites us not just to look, but to feel. And that may be why her legacy, like the glowing lines of her neon signs, continues to shine brightly in the landscape of contemporary art.