High Art, Haute Couture: When Artists and Fashion Collide

By Emilia Novak

Art and fashion have always shared a secret language. One works on canvas, the other on the body, yet both are concerned with vision, identity, and storytelling. They cross paths more often than we realize—from couture houses inviting celebrated artists into their ateliers to streetwear brands turning graffiti into global style. Think of surrealist Salvador Dalí teaming up with Elsa Schiaparelli in the 1930s, or pop powerhouse Takashi Murakami covering Louis Vuitton bags with smiling cartoon flowers. These collaborations blur the line between atelier and gallery, making clothing and accessories into unexpected art objects.

Today, many of the world’s most memorable fashion moments were born not in design studios alone, but in the fertile overlap between two creative worlds. The partnership benefits both sides: luxury brands gain cultural credibility and artistic edge, while artists reach audiences who carry their work on shoulders, wrists, and runways. What follows is a journey through some of the most fascinating collisions of high art and haute couture—moments when imagination leapt from the studio to the street.

Surreal Beginnings: Dalí and Schiaparelli Rewrite the Rules

One of the earliest and most influential unions of art and fashion emerged from the fearless imaginations of Elsa Schiaparelli and Salvador Dalí. In the late 1930s, the Italian couturière and the Spanish surrealist produced garments that blurred the line between couture and conceptual art, reshaping what clothing could communicate.

Their most famous piece, the Lobster Dress of 1937, paired a refined white organza silhouette with a large red lobster painted by Dalí. Equal parts elegant and absurd, it became a symbol of their shared wit—especially after Dalí joked about adding real mayonnaise to the design, an idea Schiaparelli wisely declined but which perfectly captured their playful rapport.

Equally audacious was the Shoe Hat: a high-heeled pump worn upside-down atop the head, inspired by a whimsical photograph of Dalí balancing a shoe on himself. Museums later praised it as “the height of Surrealist absurdity,” a sculptural object masquerading as fashion.

Their collaborations continued with the Skeleton Dress, whose padded bones traced the body’s anatomy, and a 1937 evening coat embroidered with Jean Cocteau’s poetic imagery—garments that turned the wearer into a walking surrealist tableau.

Their influence endures. Lady Gaga’s lobster headpiece paid homage to their legacy, while the modern House of Schiaparelli continually revisits their surreal motifs. Together, Schiaparelli and Dalí proved that fashion can be humorous, philosophical, and provocatively artistic all at once.

Pop Art Steps Onto the Catwalk

By the 1960s, the relationship between art and fashion took a bold leap into popular culture. Designers were not only collaborating with artists—they were directly quoting them.

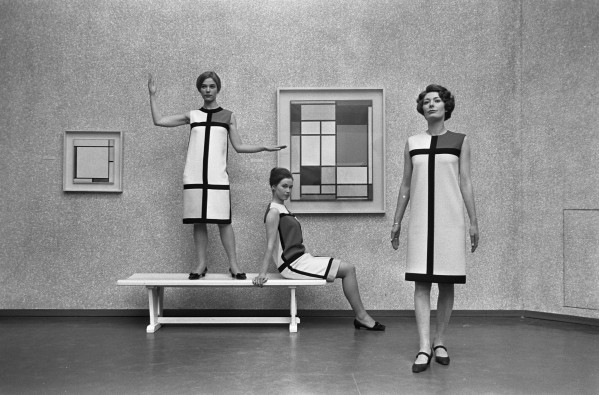

One landmark moment arrived when Yves Saint Laurent debuted his 1965 Mondrian Collection. The dresses—sleek wool shifts divided into blocks of primary color—looked like Piet Mondrian’s canvases brought to life. Minimalist in cut yet painterly in effect, the collection stunned critics and became an instant cultural phenomenon. It marked a turning point: art was no longer just inspiration; it was an integral part of the garment’s identity.

Meanwhile, Pop Art blurred distinctions even further. Andy Warhol’s iconic prints of Marilyn Monroe and Campbell’s Soup cans, originally meant to critique consumerism, found themselves on dresses, accessories, and even disposable “Souper Dresses” sold as novelty fashion items. His imagery—bold, repetitive, instantly recognizable—fit naturally into fashion’s visual language.

By the 1980s, designer Stephen Sprouse, a friend and collaborator of Warhol, began licensing Warhol’s prints—graffiti-like camouflage patterns, Day-Glo accents—and turning them into neon clubwear. These pieces captured the energy of downtown New York, where the boundaries between art, nightlife, and fashion dissolved into a single shimmering scene.

This era paved the way for the explosion of formal artist collaborations that would soon redefine the luxury sector.

Louis Vuitton’s Era of Artistic Reinvention

In the early 2000s, Louis Vuitton reshaped the luxury landscape by making artist collaborations central to its identity. Under Marc Jacobs, the house invited contemporary artists to reinterpret the monogram, transforming classic handbags into coveted art objects and setting a new creative standard for the industry.

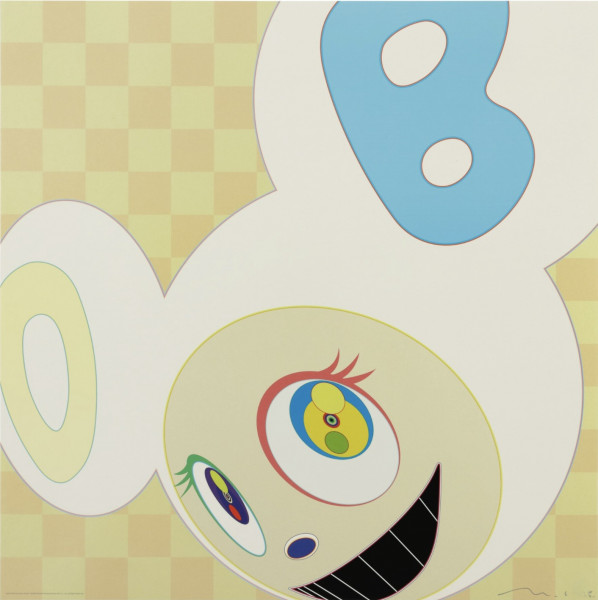

The most influential partnership arrived in 2003, when Jacobs collaborated with Takashi Murakami. Famous for his exuberant “Superflat” aesthetic and candy-bright characters, Murakami infused Vuitton’s brown canvas with playful Pop energy. His Multicolore Monogram—thirty-three vivid hues scattered on white or black backgrounds—felt like a joyful explosion, further amplified by kawaii cherry blossoms, smiling cherries, and cartoon figures that read like manga rendered in leather. The shift was seismic. The monogram suddenly felt youthful, rebellious, and irresistibly contemporary. The line became a global phenomenon, reportedly surpassing $300 million in its first year, cementing Murakami’s status in fashion and permanently expanding Vuitton’s cultural reach.

Murakami didn’t stop at accessories: he created window displays, animated films, pop-ups, and even the mascot Mr. DOB, allowing Vuitton to step fully into his imaginative universe.

Jacobs had already laid the groundwork with Stephen Sprouse, whose graffiti-covered neon monogram bags became instant cult favorites. In 2012, Yayoi Kusama followed with an all-encompassing collaboration that drenched handbags, coats, shoes, and entire storefronts in her hypnotic polka dots—complete with life-size Kusama figures “painting” the displays.

These partnerships grew into a defining Vuitton tradition. Artists such as Richard Prince, Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman, and Urs Fischer each brought their visual languages to the house, ushering in a new era where fashion operates not just as luxury, but as cultural curator.

When the Runway Becomes an Art Exhibition: Dior’s Vision

If Louis Vuitton pioneered the artist-collaboration model in accessories, Dior elevated it to the level of theatrical spectacle on the runway. In recent years, Dior’s artistic partnerships have turned entire fashion shows into immersive installations.

Maria Grazia Chiuri’s Spring/Summer 2020 couture show, created with feminist artist Judy Chicago, exemplified this approach. Set inside the Musée Rodin, the show featured a monumental inflatable goddess figure surrounded by embroidered banners posing the question, “What If Women Ruled the World?” Models walked through a womb-like architectural structure designed entirely by Chicago, merging couture with feminist art in a seamless dialogue. After the show, the installation remained open to the public as a stand-alone artwork, proving how seriously Dior treats its artistic collaborations.

Kim Jones, the artistic director of Dior Men, has also made collaboration a hallmark of his work. His debut collection featured KAWS, who redesigned the house’s bee emblem and created a towering 33-foot floral sculpture of his “BFF” character for the runway. Later seasons saw Jones working with Daniel Arsham, whose eroded plaster sculptures inspired accessories and set designs; Kenny Scharf, whose hand-drawn cartoons appeared on printed garments; Hajime Sorayama, who built a gleaming giant robot woman as a runway centrepiece; and painter Peter Doig, who applied his distinctive brushwork to custom coats and contributed paintings to the staging. This ongoing infusion of contemporary art has made Dior’s shows cultural events that feel as much like biennials as they do fashion presentations.

These collaborations offer viewers a richer experience, one that blends fashion with sculpture, painting, performance, and architecture. They acknowledge that modern luxury consumers want more than products—they want immersion, meaning, and a sense of participating in culture.

Street Art to Streetwear: When Graffiti Goes Glam

Street art’s journey from underground rebellion to global fashion language has reshaped both worlds. What once existed on train cars and alley walls now strides down runways and appears on luxury accessories, proving how profoundly graffiti aesthetics have entered mainstream style.

A defining moment came during Alexander McQueen’s Spring 1999 show. As Shalom Harlow stood on a slowly rotating platform, two robotic arms sprayed her pristine white dress with black and neon-yellow paint. It felt like performance art colliding with controlled chaos—an unmistakable gesture of street culture breaking into haute couture.

Decades before this, streetwear had already begun bridging the gap. In the 1980s, Stüssy’s handwritten logo carried graffiti’s rebellious visual language straight into everyday fashion. By the 2000s, Supreme amplified the movement through collaborations with Basquiat, Keith Haring, and KAWS. Their imagery—crowns, radiant figures, cartoon-like characters—moved from gallery spaces to hoodies, T-shirts, and skate decks, becoming collectible cultural artefacts.

High fashion quickly followed. Louis Vuitton revived Stephen Sprouse’s graffiti lettering in riotous neon. Gucci invited Trevor Andrew, known as GucciGhost, to tag its monogram bags, jackets, and dresses with playful spray-painted irreverence. Moncler’s partnerships with artists such as KAWS and Futura transformed technical winter jackets into bold, graphic canvases.

Meanwhile, collaborations keep Basquiat and Haring firmly in the cultural conversation. Coach’s Basquiat collection introduced his crown and rapid-fire lines to new generations, while Haring’s exuberant characters appear on everything from UNIQLO tees to luxury sneakers.

The allure lies in the union of raw, expressive street energy with fashion’s craftsmanship and reach—creating wearable art that feels immediate, urban, and unmistakably alive.

Why These Collaborations Matter

Beyond the spectacle and the commercial success, the union of art and fashion reflects something more profound. It shows how creativity moves fluidly across mediums, adapting and reinventing itself in response to cultural shifts. Fashion gains depth and intellectual resonance when infused with the sensibilities of fine art. Artists gain new platforms, new audiences, and new ways to express their ideas—whether on a runway, a handbag, or a denim jacket.

Of course, not every collaboration succeeds. Some are little more than superficial marketing exercises. But the ones that endure—the Schiaparelli–Dalí gowns, the Mondrian dresses, the Murakami monograms, the Dior installations—resonate because they are built on genuine creative synergy and mutual respect. They tell stories, provoke questions, and shape visual culture.

A Continuing Conversation

From Schiaparelli’s surreal gowns to Murakami’s technicolor monograms, from Dior’s immersive runways to graffiti-infused streetwear, the intersection of art and fashion remains one of the most dynamic frontiers of creativity. Artists and designers learn from each other, borrow from each other, and push each other to think more boldly.

A dress can become a painting. A handbag can become a sculpture. A runway can become a gallery. And the street, as always, becomes the world’s most democratic museum.

As long as artists seek new canvases and designers seek new stories, the collision between high art and haute couture will continue—brilliant, daring, and endlessly inspiring.

By Emilia Novak

Art and fashion have always shared a secret language. One works on canvas, the other on the body, yet both are concerned with vision, identity, and storytelling. They cross paths more often than we realize—from couture houses inviting celebrated artists into their ateliers to streetwear brands turning graffiti into global style. Think of surrealist Salvador Dalí teaming up with Elsa Schiaparelli in the 1930s, or pop powerhouse Takashi Murakami covering Louis Vuitton bags with smiling cartoon flowers. These collaborations blur the line between atelier and gallery, making clothing and accessories into unexpected art objects.

Today, many of the world’s most memorable fashion moments were born not in design studios alone, but in the fertile overlap between two creative worlds. The partnership benefits both sides: luxury brands gain cultural credibility and artistic edge, while artists reach audiences who carry their work on shoulders, wrists, and runways. What follows is a journey through some of the most fascinating collisions of high art and haute couture—moments when imagination leapt from the studio to the street.

Surreal Beginnings: Dalí and Schiaparelli Rewrite the Rules

One of the earliest and most influential unions of art and fashion emerged from the fearless imaginations of Elsa Schiaparelli and Salvador Dalí. In the late 1930s, the Italian couturière and the Spanish surrealist produced garments that blurred the line between couture and conceptual art, reshaping what clothing could communicate.

Their most famous piece, the Lobster Dress of 1937, paired a refined white organza silhouette with a large red lobster painted by Dalí. Equal parts elegant and absurd, it became a symbol of their shared wit—especially after Dalí joked about adding real mayonnaise to the design, an idea Schiaparelli wisely declined but which perfectly captured their playful rapport.

Equally audacious was the Shoe Hat: a high-heeled pump worn upside-down atop the head, inspired by a whimsical photograph of Dalí balancing a shoe on himself. Museums later praised it as “the height of Surrealist absurdity,” a sculptural object masquerading as fashion.

Their collaborations continued with the Skeleton Dress, whose padded bones traced the body’s anatomy, and a 1937 evening coat embroidered with Jean Cocteau’s poetic imagery—garments that turned the wearer into a walking surrealist tableau.

Their influence endures. Lady Gaga’s lobster headpiece paid homage to their legacy, while the modern House of Schiaparelli continually revisits their surreal motifs. Together, Schiaparelli and Dalí proved that fashion can be humorous, philosophical, and provocatively artistic all at once.

Pop Art Steps Onto the Catwalk

By the 1960s, the relationship between art and fashion took a bold leap into popular culture. Designers were not only collaborating with artists—they were directly quoting them.

One landmark moment arrived when Yves Saint Laurent debuted his 1965 Mondrian Collection. The dresses—sleek wool shifts divided into blocks of primary color—looked like Piet Mondrian’s canvases brought to life. Minimalist in cut yet painterly in effect, the collection stunned critics and became an instant cultural phenomenon. It marked a turning point: art was no longer just inspiration; it was an integral part of the garment’s identity.

Meanwhile, Pop Art blurred distinctions even further. Andy Warhol’s iconic prints of Marilyn Monroe and Campbell’s Soup cans, originally meant to critique consumerism, found themselves on dresses, accessories, and even disposable “Souper Dresses” sold as novelty fashion items. His imagery—bold, repetitive, instantly recognizable—fit naturally into fashion’s visual language.

By the 1980s, designer Stephen Sprouse, a friend and collaborator of Warhol, began licensing Warhol’s prints—graffiti-like camouflage patterns, Day-Glo accents—and turning them into neon clubwear. These pieces captured the energy of downtown New York, where the boundaries between art, nightlife, and fashion dissolved into a single shimmering scene.

This era paved the way for the explosion of formal artist collaborations that would soon redefine the luxury sector.

Louis Vuitton’s Era of Artistic Reinvention

In the early 2000s, Louis Vuitton reshaped the luxury landscape by making artist collaborations central to its identity. Under Marc Jacobs, the house invited contemporary artists to reinterpret the monogram, transforming classic handbags into coveted art objects and setting a new creative standard for the industry.

The most influential partnership arrived in 2003, when Jacobs collaborated with Takashi Murakami. Famous for his exuberant “Superflat” aesthetic and candy-bright characters, Murakami infused Vuitton’s brown canvas with playful Pop energy. His Multicolore Monogram—thirty-three vivid hues scattered on white or black backgrounds—felt like a joyful explosion, further amplified by kawaii cherry blossoms, smiling cherries, and cartoon figures that read like manga rendered in leather. The shift was seismic. The monogram suddenly felt youthful, rebellious, and irresistibly contemporary. The line became a global phenomenon, reportedly surpassing $300 million in its first year, cementing Murakami’s status in fashion and permanently expanding Vuitton’s cultural reach.

Murakami didn’t stop at accessories: he created window displays, animated films, pop-ups, and even the mascot Mr. DOB, allowing Vuitton to step fully into his imaginative universe.

Jacobs had already laid the groundwork with Stephen Sprouse, whose graffiti-covered neon monogram bags became instant cult favorites. In 2012, Yayoi Kusama followed with an all-encompassing collaboration that drenched handbags, coats, shoes, and entire storefronts in her hypnotic polka dots—complete with life-size Kusama figures “painting” the displays.

These partnerships grew into a defining Vuitton tradition. Artists such as Richard Prince, Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman, and Urs Fischer each brought their visual languages to the house, ushering in a new era where fashion operates not just as luxury, but as cultural curator.

When the Runway Becomes an Art Exhibition: Dior’s Vision

If Louis Vuitton pioneered the artist-collaboration model in accessories, Dior elevated it to the level of theatrical spectacle on the runway. In recent years, Dior’s artistic partnerships have turned entire fashion shows into immersive installations.

Maria Grazia Chiuri’s Spring/Summer 2020 couture show, created with feminist artist Judy Chicago, exemplified this approach. Set inside the Musée Rodin, the show featured a monumental inflatable goddess figure surrounded by embroidered banners posing the question, “What If Women Ruled the World?” Models walked through a womb-like architectural structure designed entirely by Chicago, merging couture with feminist art in a seamless dialogue. After the show, the installation remained open to the public as a stand-alone artwork, proving how seriously Dior treats its artistic collaborations.

Kim Jones, the artistic director of Dior Men, has also made collaboration a hallmark of his work. His debut collection featured KAWS, who redesigned the house’s bee emblem and created a towering 33-foot floral sculpture of his “BFF” character for the runway. Later seasons saw Jones working with Daniel Arsham, whose eroded plaster sculptures inspired accessories and set designs; Kenny Scharf, whose hand-drawn cartoons appeared on printed garments; Hajime Sorayama, who built a gleaming giant robot woman as a runway centrepiece; and painter Peter Doig, who applied his distinctive brushwork to custom coats and contributed paintings to the staging. This ongoing infusion of contemporary art has made Dior’s shows cultural events that feel as much like biennials as they do fashion presentations.

These collaborations offer viewers a richer experience, one that blends fashion with sculpture, painting, performance, and architecture. They acknowledge that modern luxury consumers want more than products—they want immersion, meaning, and a sense of participating in culture.

Street Art to Streetwear: When Graffiti Goes Glam

Street art’s journey from underground rebellion to global fashion language has reshaped both worlds. What once existed on train cars and alley walls now strides down runways and appears on luxury accessories, proving how profoundly graffiti aesthetics have entered mainstream style.

A defining moment came during Alexander McQueen’s Spring 1999 show. As Shalom Harlow stood on a slowly rotating platform, two robotic arms sprayed her pristine white dress with black and neon-yellow paint. It felt like performance art colliding with controlled chaos—an unmistakable gesture of street culture breaking into haute couture.

Decades before this, streetwear had already begun bridging the gap. In the 1980s, Stüssy’s handwritten logo carried graffiti’s rebellious visual language straight into everyday fashion. By the 2000s, Supreme amplified the movement through collaborations with Basquiat, Keith Haring, and KAWS. Their imagery—crowns, radiant figures, cartoon-like characters—moved from gallery spaces to hoodies, T-shirts, and skate decks, becoming collectible cultural artefacts.

High fashion quickly followed. Louis Vuitton revived Stephen Sprouse’s graffiti lettering in riotous neon. Gucci invited Trevor Andrew, known as GucciGhost, to tag its monogram bags, jackets, and dresses with playful spray-painted irreverence. Moncler’s partnerships with artists such as KAWS and Futura transformed technical winter jackets into bold, graphic canvases.

Meanwhile, collaborations keep Basquiat and Haring firmly in the cultural conversation. Coach’s Basquiat collection introduced his crown and rapid-fire lines to new generations, while Haring’s exuberant characters appear on everything from UNIQLO tees to luxury sneakers.

The allure lies in the union of raw, expressive street energy with fashion’s craftsmanship and reach—creating wearable art that feels immediate, urban, and unmistakably alive.

Beyond the spectacle and the commercial success, the union of art and fashion reflects something more profound. It shows how creativity moves fluidly across mediums, adapting and reinventing itself in response to cultural shifts. Fashion gains depth and intellectual resonance when infused with the sensibilities of fine art. Artists gain new platforms, new audiences, and new ways to express their ideas—whether on a runway, a handbag, or a denim jacket.

Of course, not every collaboration succeeds. Some are little more than superficial marketing exercises. But the ones that endure—the Schiaparelli–Dalí gowns, the Mondrian dresses, the Murakami monograms, the Dior installations—resonate because they are built on genuine creative synergy and mutual respect. They tell stories, provoke questions, and shape visual culture.

A Continuing Conversation

From Schiaparelli’s surreal gowns to Murakami’s technicolor monograms, from Dior’s immersive runways to graffiti-infused streetwear, the intersection of art and fashion remains one of the most dynamic frontiers of creativity. Artists and designers learn from each other, borrow from each other, and push each other to think more boldly.

A dress can become a painting. A handbag can become a sculpture. A runway can become a gallery. And the street, as always, becomes the world’s most democratic museum.

As long as artists seek new canvases and designers seek new stories, the collision between high art and haute couture will continue—brilliant, daring, and endlessly inspiring.