From Self-Portraits to Selfies: The Evolution of Self-Expression in Art

By Nana Japaridze

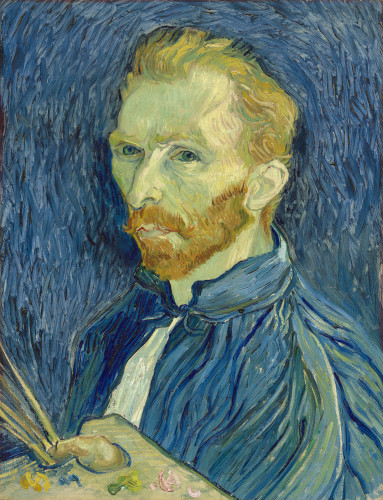

In 1660, Rembrandt painted himself with unflinching honesty. In this self-portrait, he shows every furrow and fold of age. He had suffered loss and bankruptcy by then, and his weary gaze is almost pained with introspection. Rembrandt painted over 40 self-portraits in his life – essentially keeping an artist’s diary on canvas. Centuries later, Vincent van Gogh similarly turned the camera on himself. His 1889 Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear immortalizes a bandage and fur cap after a famous breakdown. Both artists treated self-portraiture as a serious art form, not a mere snapshot of vanity.

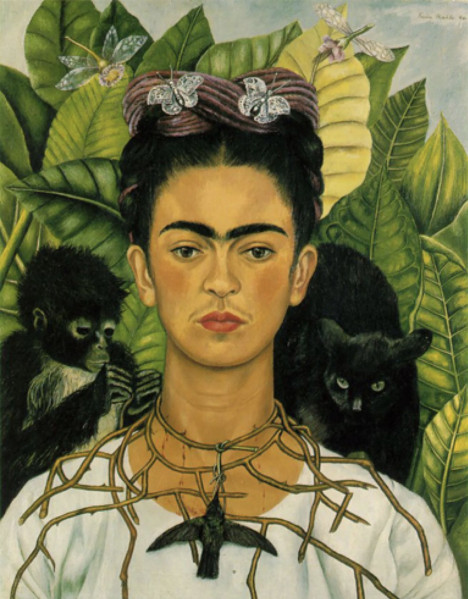

Likewise, Frida Kahlo in the 20th century wove symbolism into her self-images. In one famous 1940 painting she draped a hummingbird on her thorn necklace (evoking rebirth and hope) while a black cat prowls ominously behind her – a playful bad-luck omen. Kahlo once confessed, “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.” Her work shows that even before social media, the artist’s face could carry stories, icons, and even humor.

By contrast, today anyone can be their own photographer. In Rembrandt’s time, only trained painters could self-portrait – now we all have that wherewithal through our smartphones. It’s estimated we snap about one million selfies a day. The urge hasn’t gone away: one museum director put it well—“for the last five centuries, humans have had this compulsion to create images of themselves and share them; the only thing that has changed is the way that we do it.” In other words, artists’ centuries-old tradition of self-examination has simply gone digital.

Museums and the public have eagerly joined in. Instagram campaigns like #MuseumSelfieDay invite people to take funny selfies beside famous artworks. Art institutions even host selfie-centric exhibits. For example, London’s 2017 show From Selfie to Self-Expression traced self-portraits from Rembrandt to Cindy Sherman, and a Vermont center’s Art of the Selfie exhibition featured works by Sherman and Marina Abramović. In these shows, the line between “high art” and the Instagram snapshot blurs deliberately. (Ironically, some artists like Abramović have also staged “no selfie” shows – locking phones in lockers so visitors must look up at the canvas!)

Today’s museums are full of people taking selfies. One curator marveled that selfie-taking “is easily the most expansionist form of visual communication … we can’t ignore it as a cultural institution.” On social media, ordinary visitors join the fun (remember Barack Obama grinning in that famous group selfie? It was deemed so historic it went into exhibitions). Indeed, museums now actively encourage selfie–friendly displays, from selfie spot mirrors to cheeky captions by artworks. A single hashtag can flood galleries with crowds of joyous self-expressers – proof that self-portraiture lives on beyond the studio.

Many celebrated contemporary artists have embraced (or played with) the selfie era. For example:

- Cindy Sherman – A chameleon of self-image for decades, Sherman stunned the art world in 2017 when she suddenly made her private Instagram public. Her feed showed bizarre filtered selfies (hospital scenes, flower filters) that held up a dark mirror to our era of self-obsession. Sherman had essentially pioneered the selfie decades before social media, and her Instagram “selfies” are full of her trademark humor and role-playing.

- Ai Weiwei – The activist-artist uses selfies and snapshots as tools of protest. He posts everyday photos and, since 2015, hundreds of images of refugees fleeing conflict. In 2017 an Amsterdam gallery even exhibited his Instagram feed: the “#SafePassage” show displayed Ai’s phone snapshots of refugee camps alongside his sculptures, turning social media snaps into installation art.

- Marina Abramović – The grand dame of performance art has had an on-again, off-again relationship with selfies. She once declared “Instagram is not art,” yet she now harnesses tech. In 2019 Abramović launched The Rising, a climate-change app starring her own avatar in a melting ice tank. The game challenges users to pledge eco-friendly acts (turn off lights, recycle) to save her virtual self. It’s a clever twist: her own image becomes a plea for action, bridging performance and interactivity.

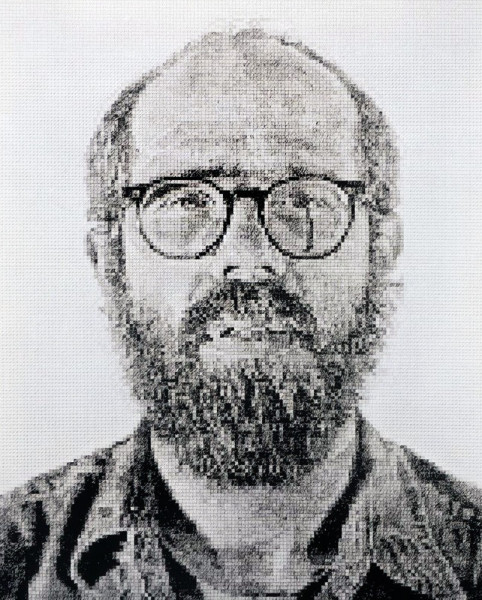

- Chuck Close – Famous for enormous grid-like portraits, Close took photography to an extreme. Early on he snapped countless Polaroids and photographs (even of his own face) then painstakingly painted them square by square. His final paintings read like giant pixelated selfies – you might only recognize the sitter (often himself or friends) when you step back. In effect, Close was doing high-art versions of the selfie long before it was a hashtag.

Each of these artists shows that the spirit of the selfie – playing with identity, media, and the self’s gaze – can fuel serious art. Some works even invite visitors to participate, flipping the camera on the audience. The camera in your hand has become just another brush or stage prop.

In the end, nothing about self-portraiture is new – only the tools have changed. From the solemn mirrors of Rembrandt’s studio to Kahlo’s symbolic animal companions, from Sherman’s character-strewn photos to an iPhone held above a museum floor – people are still, five centuries on, fascinated by their own image. The camera may have made it instant and ubiquitous, but the human compulsion to create and share images of ourselves remains as strong as ever.

By Nana Japaridze

In 1660, Rembrandt painted himself with unflinching honesty. In this self-portrait, he shows every furrow and fold of age. He had suffered loss and bankruptcy by then, and his weary gaze is almost pained with introspection. Rembrandt painted over 40 self-portraits in his life – essentially keeping an artist’s diary on canvas. Centuries later, Vincent van Gogh similarly turned the camera on himself. His 1889 Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear immortalizes a bandage and fur cap after a famous breakdown. Both artists treated self-portraiture as a serious art form, not a mere snapshot of vanity.

Likewise, Frida Kahlo in the 20th century wove symbolism into her self-images. In one famous 1940 painting she draped a hummingbird on her thorn necklace (evoking rebirth and hope) while a black cat prowls ominously behind her – a playful bad-luck omen. Kahlo once confessed, “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.” Her work shows that even before social media, the artist’s face could carry stories, icons, and even humor.

By contrast, today anyone can be their own photographer. In Rembrandt’s time, only trained painters could self-portrait – now we all have that wherewithal through our smartphones. It’s estimated we snap about one million selfies a day. The urge hasn’t gone away: one museum director put it well—“for the last five centuries, humans have had this compulsion to create images of themselves and share them; the only thing that has changed is the way that we do it.” In other words, artists’ centuries-old tradition of self-examination has simply gone digital.

Museums and the public have eagerly joined in. Instagram campaigns like #MuseumSelfieDay invite people to take funny selfies beside famous artworks. Art institutions even host selfie-centric exhibits. For example, London’s 2017 show From Selfie to Self-Expression traced self-portraits from Rembrandt to Cindy Sherman, and a Vermont center’s Art of the Selfie exhibition featured works by Sherman and Marina Abramović. In these shows, the line between “high art” and the Instagram snapshot blurs deliberately. (Ironically, some artists like Abramović have also staged “no selfie” shows – locking phones in lockers so visitors must look up at the canvas!)

Today’s museums are full of people taking selfies. One curator marveled that selfie-taking “is easily the most expansionist form of visual communication … we can’t ignore it as a cultural institution.” On social media, ordinary visitors join the fun (remember Barack Obama grinning in that famous group selfie? It was deemed so historic it went into exhibitions). Indeed, museums now actively encourage selfie–friendly displays, from selfie spot mirrors to cheeky captions by artworks. A single hashtag can flood galleries with crowds of joyous self-expressers – proof that self-portraiture lives on beyond the studio.

Many celebrated contemporary artists have embraced (or played with) the selfie era. For example:

- Cindy Sherman – A chameleon of self-image for decades, Sherman stunned the art world in 2017 when she suddenly made her private Instagram public. Her feed showed bizarre filtered selfies (hospital scenes, flower filters) that held up a dark mirror to our era of self-obsession. Sherman had essentially pioneered the selfie decades before social media, and her Instagram “selfies” are full of her trademark humor and role-playing.

- Ai Weiwei – The activist-artist uses selfies and snapshots as tools of protest. He posts everyday photos and, since 2015, hundreds of images of refugees fleeing conflict. In 2017 an Amsterdam gallery even exhibited his Instagram feed: the “#SafePassage” show displayed Ai’s phone snapshots of refugee camps alongside his sculptures, turning social media snaps into installation art.

- Marina Abramović – The grand dame of performance art has had an on-again, off-again relationship with selfies. She once declared “Instagram is not art,” yet she now harnesses tech. In 2019 Abramović launched The Rising, a climate-change app starring her own avatar in a melting ice tank. The game challenges users to pledge eco-friendly acts (turn off lights, recycle) to save her virtual self. It’s a clever twist: her own image becomes a plea for action, bridging performance and interactivity.

- Chuck Close – Famous for enormous grid-like portraits, Close took photography to an extreme. Early on he snapped countless Polaroids and photographs (even of his own face) then painstakingly painted them square by square. His final paintings read like giant pixelated selfies – you might only recognize the sitter (often himself or friends) when you step back. In effect, Close was doing high-art versions of the selfie long before it was a hashtag.

Each of these artists shows that the spirit of the selfie – playing with identity, media, and the self’s gaze – can fuel serious art. Some works even invite visitors to participate, flipping the camera on the audience. The camera in your hand has become just another brush or stage prop.

In the end, nothing about self-portraiture is new – only the tools have changed. From the solemn mirrors of Rembrandt’s studio to Kahlo’s symbolic animal companions, from Sherman’s character-strewn photos to an iPhone held above a museum floor – people are still, five centuries on, fascinated by their own image. The camera may have made it instant and ubiquitous, but the human compulsion to create and share images of ourselves remains as strong as ever.