Names We Know, Faces We Don’t: The Art of Anonymity

By Nana Japaridze

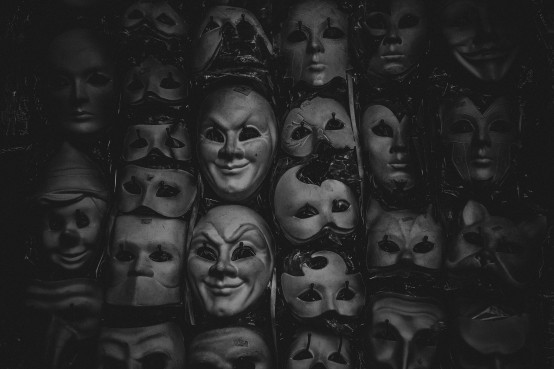

In the annals of art history, intrigue often wears a disguise. From Dadaists in drag to masked street vandals, artists have long hidden behind alter egos, pseudonyms, and second selves. These secret identities can serve as shields, mirrors, or keys—tools to unlock different voices, challenge convention, and sometimes poke fun at the art world itself.

Art history, in this sense, reads like a detective story: mysterious signatures, cryptic graffiti tags, and double lives that blur where the artist ends and the character begins. Why do creatives feel compelled to split themselves in two? Some wish to satirize identity, others to escape fame or censorship, and a few simply crave the freedom that comes from pretending to be someone else. Behind every alias lies an artistic revelation. Let’s lift a few of these masks and discover what happens when artists dare to hide in plain sight.

The Dada Detective: Marcel Duchamp Becomes Rrose Sélavy

Paris, 1920s. Among the avant-garde, a new name begins to appear: Rrose Sélavy. The signature, elegant and witty, belonged not to a woman but to Marcel Duchamp, the mischievous pioneer of Dada and conceptual art. Pronounced like “Rose, c’est la vie”—“Rose, that’s life”—the name also hides another pun: “Eros, c’est la vie.”

Duchamp wasn’t simply playing dress-up. When photographer Man Ray captured him as Rrose in 1921—complete with velvet hat, makeup, and a sly smile—the result was both portrait and provocation. Rrose Sélavy was a living artwork: a persona through which Duchamp could question gender, authorship, and the idea of originality itself.

He began signing works as Rrose, including the sculpture Why Not Sneeze, Rose Sélavy? (1921). Years earlier, he had shocked the art world by signing a urinal “R. Mutt” and submitting it as Fountain (1917). Through these aliases, Duchamp mocked the cult of the artist’s name. As one critic wrote, “Rrose Sélavy—‘Eros, that’s life’—summed up Duchamp’s art.”

Rrose allowed him to step outside himself, to turn identity into a game and art into a masquerade. With her, Duchamp proved that creation could be as much about who is speaking as what is being said.

The Man Behind “SAMO”: Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Streetwise Persona

Half a century later, in late 1970s New York, another alias began to appear—this time spray-painted on city walls: SAMO©. The mysterious graffiti slogans read like surreal urban poems:

“SAMO© as an end to mindwash religion, nowhere politics, and bogus philosophy.”

Behind the tag were two teenagers, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Al Diaz. SAMO—short for “Same Old”—was their invented brand, part satire, part rebellion. The pseudonym let Basquiat critique the art scene while remaining invisible. The anonymity gave him confidence, turning him into an urban myth long before he was a star.

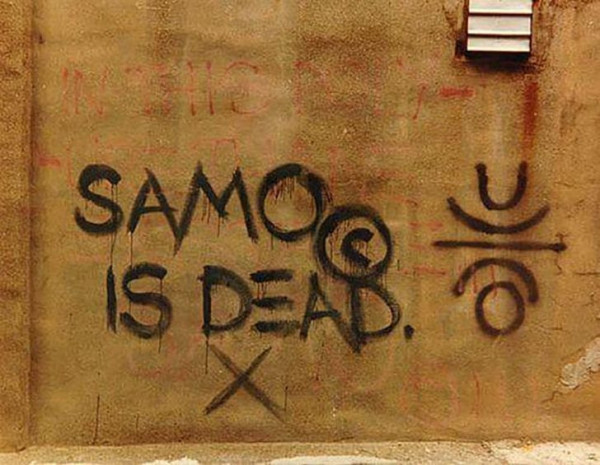

By 1980, Basquiat and Diaz fell out, and Basquiat famously sprayed “SAMO IS DEAD” across SoHo—killing off his alter ego just as his real name began to rise. Yet SAMO’s ghost lived on in his later canvases, with their urgent scrawls and poetic fragments.

SAMO was both mask and training ground—a space for Basquiat to experiment, provoke, and be heard. As Duchamp had done before him, he used a pseudonym to critique the system from within. When he finally unmasked himself, the art world was ready to listen.

The Art of Anonymity: Banksy’s Hidden Face

If Duchamp played with identity and Basquiat used it as armor, Banksy turned anonymity into a global performance. The British street artist is now a cultural icon precisely because no one knows who he is. His stenciled images—children with balloons, riot police with flowers—appear overnight on walls from London to Los Angeles, unsigned but unmistakable.

In an age of constant exposure, Banksy’s invisibility feels revolutionary. He once said, “If you want to say something and have people listen, you have to wear a mask.” The mask protects him legally, but also philosophically. By removing the artist’s face, Banksy forces viewers to focus on the work’s message—its satire of consumerism, war, and hypocrisy—rather than on fame.

His anonymity is itself a masterpiece of storytelling. The guessing game of “Who is Banksy?” has fueled his myth as much as his art. Even his most public gestures, like the self-shredding of Girl with Balloon at Sotheby’s, depend on secrecy for their impact.

Banksy’s pseudonym has become more than protection—it’s a mirror. It reflects our fascination with celebrity, authorship, and truth. By staying hidden, Banksy has made the mask part of the message.

Street Art’s Shadow Network: Blek le Rat, Invader, and KAWS

Banksy’s mystery belongs to a long lineage of street artists who turned pseudonyms into legends.

In 1980s Paris, Blek le Rat (real name Xavier Prou) stenciled black rats across city walls, declaring, “Rats are the only free animals in the city.” His name played on a comic-book hero (Blek le Roc) and on wordplay—“rat” is “art” reversed. To the public, Blek’s rats became symbols of resistance and freedom. His anonymity made him mythic, and his influence on Banksy undeniable.

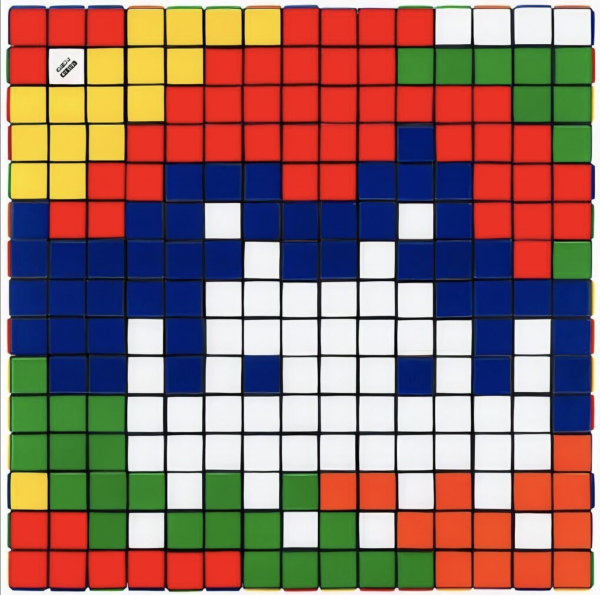

Later, another French artist emerged: Invader. Since the late 1990s, he has secretly installed thousands of tiny mosaics inspired by the video game Space Invaders in over 80 cities worldwide. Disguised in a pixelated mask, Invader treats the world as his arcade, tracking each “invasion” on a personal scoreboard. He once even smuggled a piece into the Louvre, joking that he was “the only living artist with work in the Louvre.”

Across the Atlantic, KAWS (born Brian Donnelly) began tagging his name across New York in the 1990s simply because he liked the letters. Over time, “KAWS” became his professional identity, a bridge from graffiti to galleries. His cartoonish sculptures and designer collaborations made him a global brand. Unlike other street artists, KAWS didn’t shed his alias—he grew into it. His pseudonym became his signature, proof that an alter ego can evolve from anonymity to authorship.

In these stories, the alias isn’t a mask to hide behind—it’s a stage name, a persona that gives shape and continuity to the artist’s voice.

Performing Identity: Grayson Perry’s “Claire” and the Guerrilla Girls

Not every alter ego hides; some reveal by exaggeration. British artist Grayson Perry, famous for his ceramics and social commentary, often appears as his alter ego Claire, dressed in flamboyant gowns and wigs. Through Claire, Perry explores gender, class, and self-expression with humor and empathy.

“Claire,” he has said, “can be whoever she wants—a matriarch, a protester, a freedom fighter.” She’s not a disguise but an expansion—a way for Perry to embody ideas about masculinity and identity through performance. His photograph Mother of All Battles (1996), depicting Claire as a defiant housewife clutching a gun, combines satire and sincerity.

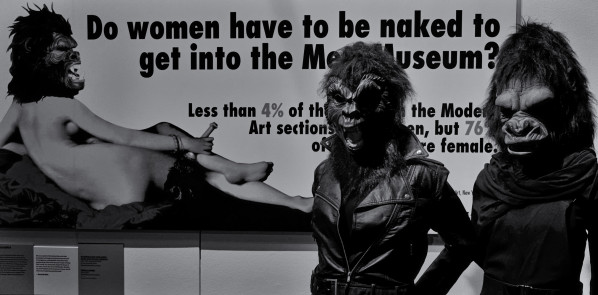

If Perry’s alter ego personalizes identity, the Guerrilla Girls collectivize it. Since 1985, this anonymous group of feminist artists has appeared in public wearing gorilla masks and signing posters with the names of famous women artists like Frida Kahlo or Käthe Kollwitz. Their anonymity is not about hiding but amplifying. By removing individual egos, they make the message louder: challenging sexism, racism, and inequality in the art world.

Their famous poster asked, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?”—pointing out that less than 5% of the artists in its Modern Art section were women, but 85% of the nudes were female. The Guerrilla Girls’ masked faces became symbols of resistance, proving that invisibility can be a powerful form of presence.

Unmasking the Magic

From Duchamp’s Rrose Sélavy to Banksy’s ghostly persona, from Basquiat’s SAMO to Grayson Perry’s Claire, artists have long found creative truth through disguise. The alter ego liberates them from expectation and fear—it allows them to experiment, provoke, and speak freely.

Marcel Duchamp used Rrose to satirize art’s obsession with the “genius” name. Basquiat used SAMO to gain a voice in a world that didn’t yet see him. Banksy’s anonymity protects his message from celebrity’s glare. Grayson Perry’s Claire makes visible the fluidity of identity, while the Guerrilla Girls turn the act of hiding into activism.

Their double lives remind us that art itself is a transformation. A urinal becomes art when signed “R. Mutt.” A graffiti slogan becomes poetry when tagged “SAMO.” A faceless protest becomes history when carried out by masked women.

Ultimately, alter egos show that truth in art often hides behind fiction. They blur boundaries between the artist and the work, between the real and the performed. They make us lean closer, searching for clues—an act that turns us, too, into detectives of meaning.

As Oscar Wilde once observed, “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.” Artists have always known this. Their masks—be they velvet hats, graffiti tags, or gorilla masks—don’t conceal the truth; they reveal it, just from behind a different face.

And perhaps that’s the real magic of art’s alter egos: that through disguise, artists become even more themselves.

By Nana Japaridze

In the annals of art history, intrigue often wears a disguise. From Dadaists in drag to masked street vandals, artists have long hidden behind alter egos, pseudonyms, and second selves. These secret identities can serve as shields, mirrors, or keys—tools to unlock different voices, challenge convention, and sometimes poke fun at the art world itself.

Art history, in this sense, reads like a detective story: mysterious signatures, cryptic graffiti tags, and double lives that blur where the artist ends and the character begins. Why do creatives feel compelled to split themselves in two? Some wish to satirize identity, others to escape fame or censorship, and a few simply crave the freedom that comes from pretending to be someone else. Behind every alias lies an artistic revelation. Let’s lift a few of these masks and discover what happens when artists dare to hide in plain sight.

The Dada Detective: Marcel Duchamp Becomes Rrose Sélavy

Paris, 1920s. Among the avant-garde, a new name begins to appear: Rrose Sélavy. The signature, elegant and witty, belonged not to a woman but to Marcel Duchamp, the mischievous pioneer of Dada and conceptual art. Pronounced like “Rose, c’est la vie”—“Rose, that’s life”—the name also hides another pun: “Eros, c’est la vie.”

Duchamp wasn’t simply playing dress-up. When photographer Man Ray captured him as Rrose in 1921—complete with velvet hat, makeup, and a sly smile—the result was both portrait and provocation. Rrose Sélavy was a living artwork: a persona through which Duchamp could question gender, authorship, and the idea of originality itself.

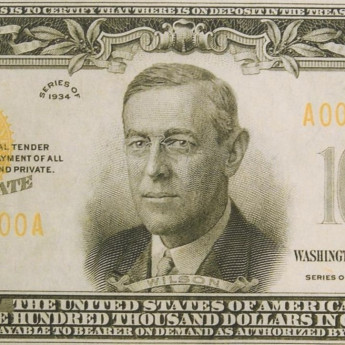

He began signing works as Rrose, including the sculpture Why Not Sneeze, Rose Sélavy? (1921). Years earlier, he had shocked the art world by signing a urinal “R. Mutt” and submitting it as Fountain (1917). Through these aliases, Duchamp mocked the cult of the artist’s name. As one critic wrote, “Rrose Sélavy—‘Eros, that’s life’—summed up Duchamp’s art.”

Rrose allowed him to step outside himself, to turn identity into a game and art into a masquerade. With her, Duchamp proved that creation could be as much about who is speaking as what is being said.

The Man Behind “SAMO”: Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Streetwise Persona

Half a century later, in late 1970s New York, another alias began to appear—this time spray-painted on city walls: SAMO©. The mysterious graffiti slogans read like surreal urban poems:

“SAMO© as an end to mindwash religion, nowhere politics, and bogus philosophy.”

Behind the tag were two teenagers, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Al Diaz. SAMO—short for “Same Old”—was their invented brand, part satire, part rebellion. The pseudonym let Basquiat critique the art scene while remaining invisible. The anonymity gave him confidence, turning him into an urban myth long before he was a star.

By 1980, Basquiat and Diaz fell out, and Basquiat famously sprayed “SAMO IS DEAD” across SoHo—killing off his alter ego just as his real name began to rise. Yet SAMO’s ghost lived on in his later canvases, with their urgent scrawls and poetic fragments.

SAMO was both mask and training ground—a space for Basquiat to experiment, provoke, and be heard. As Duchamp had done before him, he used a pseudonym to critique the system from within. When he finally unmasked himself, the art world was ready to listen.

The Art of Anonymity: Banksy’s Hidden Face

If Duchamp played with identity and Basquiat used it as armor, Banksy turned anonymity into a global performance. The British street artist is now a cultural icon precisely because no one knows who he is. His stenciled images—children with balloons, riot police with flowers—appear overnight on walls from London to Los Angeles, unsigned but unmistakable.

In an age of constant exposure, Banksy’s invisibility feels revolutionary. He once said, “If you want to say something and have people listen, you have to wear a mask.” The mask protects him legally, but also philosophically. By removing the artist’s face, Banksy forces viewers to focus on the work’s message—its satire of consumerism, war, and hypocrisy—rather than on fame.

His anonymity is itself a masterpiece of storytelling. The guessing game of “Who is Banksy?” has fueled his myth as much as his art. Even his most public gestures, like the self-shredding of Girl with Balloon at Sotheby’s, depend on secrecy for their impact.

Banksy’s pseudonym has become more than protection—it’s a mirror. It reflects our fascination with celebrity, authorship, and truth. By staying hidden, Banksy has made the mask part of the message.

Street Art’s Shadow Network: Blek le Rat, Invader, and KAWS

Banksy’s mystery belongs to a long lineage of street artists who turned pseudonyms into legends.

In 1980s Paris, Blek le Rat (real name Xavier Prou) stenciled black rats across city walls, declaring, “Rats are the only free animals in the city.” His name played on a comic-book hero (Blek le Roc) and on wordplay—“rat” is “art” reversed. To the public, Blek’s rats became symbols of resistance and freedom. His anonymity made him mythic, and his influence on Banksy undeniable.

Later, another French artist emerged: Invader. Since the late 1990s, he has secretly installed thousands of tiny mosaics inspired by the video game Space Invaders in over 80 cities worldwide. Disguised in a pixelated mask, Invader treats the world as his arcade, tracking each “invasion” on a personal scoreboard. He once even smuggled a piece into the Louvre, joking that he was “the only living artist with work in the Louvre.”

Across the Atlantic, KAWS (born Brian Donnelly) began tagging his name across New York in the 1990s simply because he liked the letters. Over time, “KAWS” became his professional identity, a bridge from graffiti to galleries. His cartoonish sculptures and designer collaborations made him a global brand. Unlike other street artists, KAWS didn’t shed his alias—he grew into it. His pseudonym became his signature, proof that an alter ego can evolve from anonymity to authorship.

In these stories, the alias isn’t a mask to hide behind—it’s a stage name, a persona that gives shape and continuity to the artist’s voice.

Performing Identity: Grayson Perry’s “Claire” and the Guerrilla Girls

Not every alter ego hides; some reveal by exaggeration. British artist Grayson Perry, famous for his ceramics and social commentary, often appears as his alter ego Claire, dressed in flamboyant gowns and wigs. Through Claire, Perry explores gender, class, and self-expression with humor and empathy.

“Claire,” he has said, “can be whoever she wants—a matriarch, a protester, a freedom fighter.” She’s not a disguise but an expansion—a way for Perry to embody ideas about masculinity and identity through performance. His photograph Mother of All Battles (1996), depicting Claire as a defiant housewife clutching a gun, combines satire and sincerity.

If Perry’s alter ego personalizes identity, the Guerrilla Girls collectivize it. Since 1985, this anonymous group of feminist artists has appeared in public wearing gorilla masks and signing posters with the names of famous women artists like Frida Kahlo or Käthe Kollwitz. Their anonymity is not about hiding but amplifying. By removing individual egos, they make the message louder: challenging sexism, racism, and inequality in the art world.

Their famous poster asked, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?”—pointing out that less than 5% of the artists in its Modern Art section were women, but 85% of the nudes were female. The Guerrilla Girls’ masked faces became symbols of resistance, proving that invisibility can be a powerful form of presence.

Unmasking the Magic

From Duchamp’s Rrose Sélavy to Banksy’s ghostly persona, from Basquiat’s SAMO to Grayson Perry’s Claire, artists have long found creative truth through disguise. The alter ego liberates them from expectation and fear—it allows them to experiment, provoke, and speak freely.

Marcel Duchamp used Rrose to satirize art’s obsession with the “genius” name. Basquiat used SAMO to gain a voice in a world that didn’t yet see him. Banksy’s anonymity protects his message from celebrity’s glare. Grayson Perry’s Claire makes visible the fluidity of identity, while the Guerrilla Girls turn the act of hiding into activism.

Their double lives remind us that art itself is a transformation. A urinal becomes art when signed “R. Mutt.” A graffiti slogan becomes poetry when tagged “SAMO.” A faceless protest becomes history when carried out by masked women.

Ultimately, alter egos show that truth in art often hides behind fiction. They blur boundaries between the artist and the work, between the real and the performed. They make us lean closer, searching for clues—an act that turns us, too, into detectives of meaning.

As Oscar Wilde once observed, “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.” Artists have always known this. Their masks—be they velvet hats, graffiti tags, or gorilla masks—don’t conceal the truth; they reveal it, just from behind a different face.

And perhaps that’s the real magic of art’s alter egos: that through disguise, artists become even more themselves.