Documenting the Undocumented: Photography as Social Commentary

By Emilia Novak

Photography often shines where words fall short. It exposes hidden communities, reframes stereotypes, and preserves spaces and moments overlooked by mainstream imagery. Across decades and continents, artists have used the camera not just to record but to comment—to make visible what society leaves in shadow.

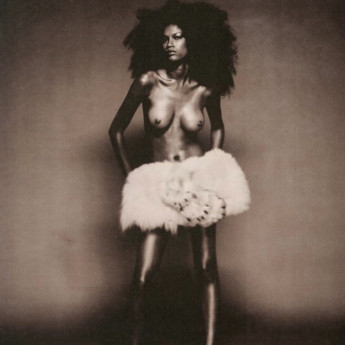

Nan Goldin’s work is inseparable from her life. In this candid portrait of two drag queens in New York, her unfiltered style captures both the defiance and fragility of queer life at the height of the AIDS crisis. Far from glamorized, the image affirms dignity and humanity, making visible those largely ignored in mainstream media. Goldin’s social diary remains a landmark in showing how the personal becomes political.

Cindy Sherman – Pregnant Woman (1991)

Sherman embodies personas to critique cultural myths. Here, she stages herself as a disheveled, heavily pregnant woman—milk-stained, rumpled, and uncomfortably direct. By exaggerating features of maternity, she dismantles the idealized “Madonna” image. Her unsettling portrayal forces viewers to confront how femininity and motherhood are constructed, exposing a reality rarely shown in public imagery.

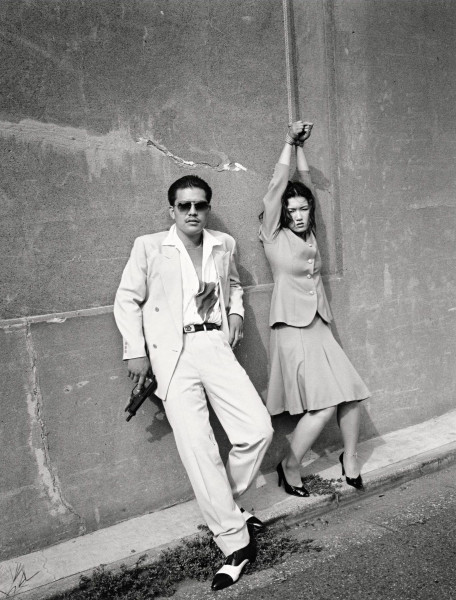

Nobuyoshi Araki – Mythology (2001)

Araki’s vast oeuvre blurs diary and social document. From bondage series to intimate chronicles of his wife’s illness, his work elevates taboo subjects into cultural commentary. Mythology continues this trajectory: erotic yet poetic, it suggests that desire, grief, and mortality are our modern myths. By documenting what Japanese society often keeps private, Araki insists these hidden truths belong in art’s record.

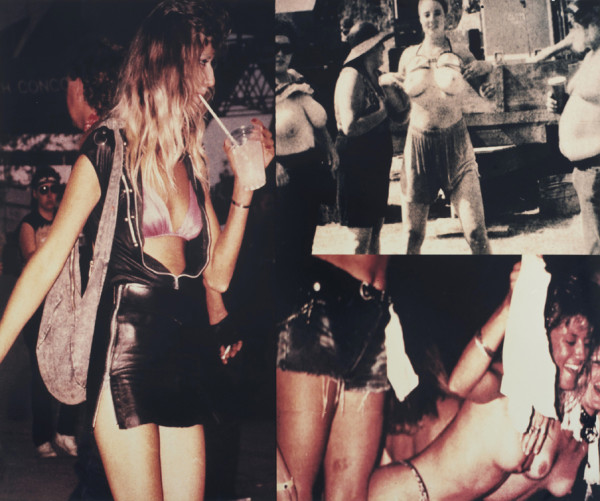

Richard Prince – Untitled (from Upstate Nudes) (1998)

Prince appropriates amateur nude snapshots, reframing them as art. The collage looks like a family album page, yet its public display exposes tensions between privacy, consent, and voyeurism. By presenting everyday, imperfect images instead of commercial ideals, Prince questions how society consumes the nude and who controls the narrative of sexuality. The unease viewers feel is itself the commentary.

Thomas Ruff – Q.i.C. (Queen in Car) (2021)

Ruff revisits a 1953 press photo of Queen Elizabeth II, showing it with and without its caption. Stripped of context, the image feels cinematic, mysterious—almost anonymous. With the caption, it transforms into a historical record. Ruff demonstrates how captions and framing dictate meaning, asking us to reconsider the reliability of press photography and the gap between reality and representation.

Candida Höfer – Historisch-Geographischer Schul-Atlas (2009)

Höfer turns her lens on grand but empty interiors—libraries, palaces, map rooms. This photograph of a Florentine palazzo, centered on an antique globe, is a meditation on knowledge and time. By documenting cultural spaces often invisible in popular imagery, she raises questions about memory, access, and preservation in the digital age. The absence of people makes the silence itself a form of commentary.

Thomas Struth – Deutsche Stadtbaukunst (2010)

Struth elevates ordinary city streets into reflections on collective memory. His monochrome photograph of a modest Japanese street, framed under the title “German Urban Architecture,” juxtaposes cultural histories and underscores the universality of urban life. By treating an unremarkable street with the same care as a monument, Struth shows that everyday architecture holds the layered stories of a society.

Bert Stern – Marilyn “Pink Roses” (The Last Sitting) (1962/2011)

Stern’s final session with Marilyn Monroe captured a rare intimacy. In Pink Roses, Monroe appears playful yet vulnerable, a woman behind the legend. Unlike her curated public persona, this image conveys fragility and humanity. It documents the undocumented side of a global icon, exposing the tension between celebrity myth and private reality—and, by extension, the culture that consumes both.

Conclusion: The Lens as a Social Mirror

From drag queens in taxis to empty map rooms, these photographers show that nothing is too hidden—or too familiar—to merit re-examination. Each uses the camera not just to capture but to question: how we see identity, how stereotypes are constructed, how spaces are remembered, how icons are consumed.

Photography as social commentary ensures that no story, however marginalized or fleeting, remains entirely untold. Each frame becomes both witness and advocate—making the invisible visible, and reminding us that behind every image lies a culture, a history, and a human truth.

By Emilia Novak

Photography often shines where words fall short. It exposes hidden communities, reframes stereotypes, and preserves spaces and moments overlooked by mainstream imagery. Across decades and continents, artists have used the camera not just to record but to comment—to make visible what society leaves in shadow.

Cindy Sherman – Pregnant Woman (1991)

Nobuyoshi Araki – Mythology (2001)

Richard Prince – Untitled (from Upstate Nudes) (1998)

Thomas Ruff – Q.i.C. (Queen in Car) (2021)

Candida Höfer – Historisch-Geographischer Schul-Atlas (2009)

Thomas Struth – Deutsche Stadtbaukunst (2010)

Bert Stern – Marilyn “Pink Roses” (The Last Sitting) (1962/2011)

Conclusion: The Lens as a Social Mirror

From drag queens in taxis to empty map rooms, these photographers show that nothing is too hidden—or too familiar—to merit re-examination. Each uses the camera not just to capture but to question: how we see identity, how stereotypes are constructed, how spaces are remembered, how icons are consumed.

Photography as social commentary ensures that no story, however marginalized or fleeting, remains entirely untold. Each frame becomes both witness and advocate—making the invisible visible, and reminding us that behind every image lies a culture, a history, and a human truth.