By Nana Japaridze

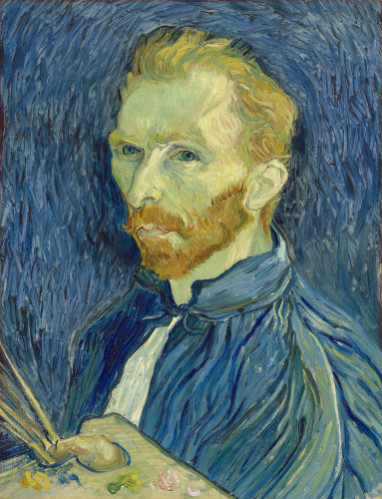

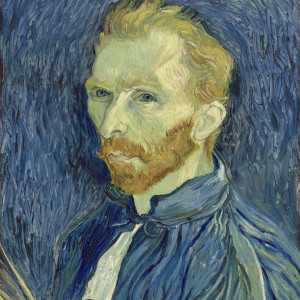

In 1660, Rembrandt painted himself with unflinching honesty. In this self-portrait, he shows every furrow and fold of age. He had suffered loss and bankruptcy by then, and his weary gaze is almost pained with introspection. Rembrandt painted over 40 self-portraits in his life – essentially keeping an artist’s diary on canvas. Centuries later, Vincent van Gogh similarly turned the camera on himself. His 1889 Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear immortalizes a bandage and fur cap after a famous breakdown. Both artists treated self-portraiture as a serious art form, not a mere snapshot of vanity.

Journal

IN FOCUS

From Self-Portraits to Selfies: The Evolution of Self-Expres...

By Nana Japaridze

In 1660, Rembrandt painted himself with unflinching honesty. In this self-portrait, he shows every furrow and fold of age. He had suffered loss and bankruptcy by then, and his weary gaze is almost pa